Whiteflag, an engaging exhibition at the Visual Arts Gallery, India Habitat Centre, showcases the works of acclaimed Maltese artist Austin Camilleri.

Organised by the High Commission of Malta, it explores the theme of migration and displacement, and at a micro level “journeys” ~ physical and spiritual ~ of people, objects, even art.

As a peripatetic artist, who has visited over 40 countries and worked across four continents, Camilleri brings a unique sensibility to his work. “The globally relevant theme of migration and displacement finds a universal echo in a fraught world beset by racial tensions and rigid borders,” says Camilleri, 44, who works simultaneously in painting, installation, sculpture, video and drawing to present ideas of time and transience.

Advertisement

The artist, who lives on the island of Gozo and works between Malta and Italy, is also a curator, founder of 356 art gallery as well as a visiting lecturer at the Faculty of Built Environment, University of Malta.

“I find it enriching to be student as well as a teacher of art,” explains the bearded Camilleri, whose works have been exhibited extensively in solo and group shows in museums, biennales, private galleries and public spaces across Europe, America and Asia.

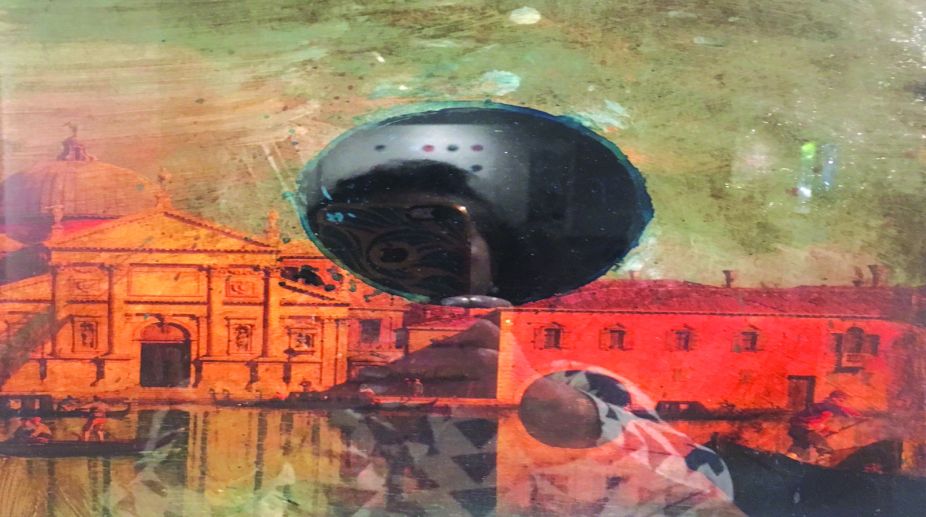

White flag is the artist’s first exhibition in India where all his 24 works~ on paper, canvas, video and sculpture ~ coalesce to present his year-long research into politics and transitory paths taken by migrants.

In some works, the artist has also clinically traced maps of migrants’ shipwreck sites by embossing, a technique that uses lead spheres from bullet cartridges. His two videos ~ Bandiera Bianca and Restoring Tiepolo ~ metaphorically capture the concepts of wait and loss.

The Tondo and Ghost Trip series forms part of a larger body of work on paper Camilleri started in 2014. “The ground of the GT series slowly shifted from hotel paper to being reproduced drawings that were eventually ‘erased’ with subsequent layers of ink and tar, emphasising the gravitational essence in dualities: from delicate marks to imbued stains of pigment,” says the versatile artist.

Drawing from a groundswell of Western art, history, popular culture and power image traditions, Camilleri also loves to infuse the element of transmutation in his works. Fascinating, therefore, is the transformation the artist has wrought for an old aluminium propeller (which he bought from a scrap dealer in Malta) by coating it in 22 carat gold leaf in his installation titled “Hope”.

“I’ve used gold to elevate the humble aluminium propeller from a pedestrian object to an aspirational one. Juxtaposing objects and interventions creates new meanings and associations,” says Camilleri, who is looking forward to travelling across India.

Is he visiting the Taj Mahal, one of the greatest works of art of all time? “Of course,” he quips adding that he’s also keen to sample Indian cuisine. “Travel is an immersive experience and I hope to experience all facets of your fascinating country through its people, food and culture.”

Perhaps the most striking feature of Camilleri’s work is the sheer diversity of mediums he leverages to convey his message, covering an entire spectrum from road tar to non-Newtonian ink to gold leaf to bullets and cartridges! Camilleri has represented Malta internationally in biennales at Paris, Brussels, Rome, Vienna, London, New York, Geneva, Munich, Ramallah, Guatemala City, and Cape Town, among others.

He often also curates exhibitions and creates interdisciplinary working with authors, composers, actors, architects and choreographers, together or separately.

The artist’s painting process, often compared to the sixth-century Western European practice of “Palimpsest”, is considered one of the earliest processes of recycling of material.

However, Camilleri is quick to clarify that he doesn’t “re-use my canvases for economic or ecological motives but rather to re-appropriate my existing work as hostage to act as new reference framework for further inception”.

Advertisement