Japan’s Path

Japan's enduring economic challenges serve as both a cautionary tale and a beacon of resilience.

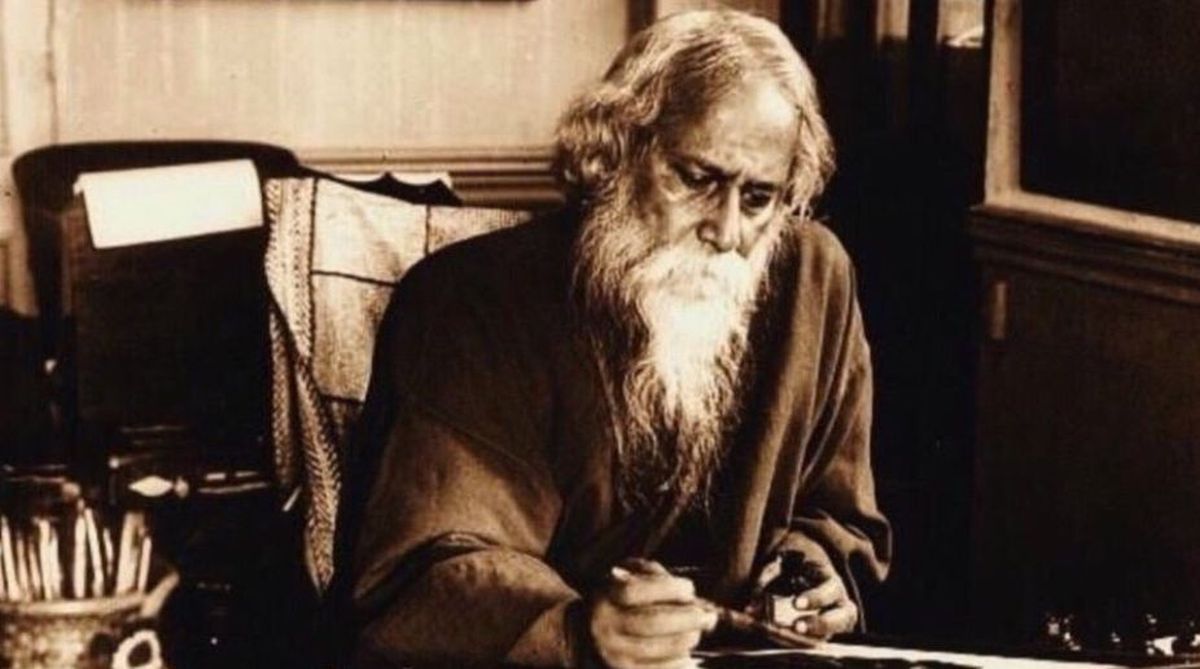

Polymath Rabindranath Tagore’s wisdom teaches us about how we need to consider the larger picture for India’s progress.

Rabindranath Tagore.

During the year-long celebrations to mark Rabindranath Tagore’s 150th birth anniversary, which concluded in New Delhi on 7 May 2012, two significant dimensions were reflected, which are vital for India’s progress. Tagore always substantiated his thoughts through observations and that enabled him to share his erudite analysis with the country.

His love for the environment revealed a spectacular chapter because the movement he initiated, was, perhaps, the very first which built up a mass environmental awareness; this was before the matter, of caring for the environment, arose in the West. There is inevitably a reason for a person to pursue the protection of the environment, which Tagore followed assiduously with passion.

When he was on his way to Japan in 1916, Tagore was dismayed to view man’s impact when he saw an oil spill over a vast area of the sea. Subsequent to this his writings reflected man’s relationship with the environment. His thoughts were conveyed when he began building Santiniketan by ensuring the main block was surrounded by nature.

Advertisement

He wished his students to delight themselves by viewing trees, birds, butterflies and all that a natural setting could offer. It was also at Santiniketan that he perpetuated the essentials of cooperation with humanity. He shared the concerns of people around him through his benevolence towards tenant peasants; he would inaugurate each ploughing season, at Santiniketan, and this highlighted his deep love for farmers who live with the natural elements.

Tagore began a festival of “The Earth”, by planting saplings in 1927. The festival would commence by his students reciting and singing his poetry.

It was on Tagore’s 80th birthday, in 1941, when he delivered a powerful speech at Santiniketan, which was titled “The crisis of civilization”. He was concerned of the change in his own attitude and that of all Indians. He articulated these changes as a “tragedy”, and he explained there were reasons.

Awareness was imperative for every citizen to learn about the larger picture which exists beyond our shores. He reasoned that our people’s direct interaction with the world was almost solely linked with English speaking people and as a consequence we were influenced by their “mighty literature” which enabled our people to form ideas about this race.

In those times the mode of learning served to Indians was not as diverse in terms of subjects; for example subjects related to science were basic and Indians could not advance further into the subject’s other branches.

Education mainly rested on English language and literature, which imparted knowledge of poets like Burke, Byron or Wordsworth and a lot was focused on Shakespeare’s plays. History was related to world history, English history and English political ideals of the 19th century. But in those early years of his life Tagore was, to begin with, impressed by evidence of liberal humanity in the character of the British.

That impression of liberal humanity gradually began to diminish when Tagore was confronted with scenes of poverty which appeared like a “stark light” and which he said “Rent my heart”. He was horrified to view “such hopeless dearth” of the most elementary needs of existence. Yet in an ironical manner it was Indian resources that fed the colonial rulers for over a century.

On another plane and tragically for India, Japan was transforming itself into a prosperous nation. This he articulated was not because the Indian intelligence was inferior to the Japanese. The great difference between these two eastern nations was because Japan was spared the “shadow of alien domination.”

Tagore juxtaposed the plight of India during his visit to Moscow when he observed “the unsparing energy with which the country tried to combat disease and illiteracy” to remove ignorance and poverty. He was pleasantly surprised to view their progress with no difference between one class and another. He marveled at the enthusiasm with which that country progressed and said it “made me happy and jealous at the same time.”

Their administration was exemplary and showed no scope for conflict of religious differences. He was impressed by the rulers of the USSR to harmonise the interests of various nationalities scattered over the country’s vast area.

He actually saw tribes who “only the other day were nomadic savages and were being encouraged to avail the benefits of civilisation, with enormous sums of money being spent for their development. He concluded that the USSR evoked a dynamic form of progress based on “cooperation” while India’s people appeared to be drifting because of “exploitation”. The movement for Independence had gradually sown its seeds which just may evoke “unrest” because the country had to first unshackle itself from colonial rule.

He yearned for a free India with the ideals of cooperation among India’s people. Till independence the country was similar to his thoughts of a banyan tree:

“O ancient banyan tree, You stand still day and night, like an ascetic at his penances…”

Advertisement