It is a new law, even by the standards of contemporary political conduct and discourse. It had been conveniently assumed at least by right thinking Indians that the polity and its ardent practitioners could not sink further. How grievously wrong were they.

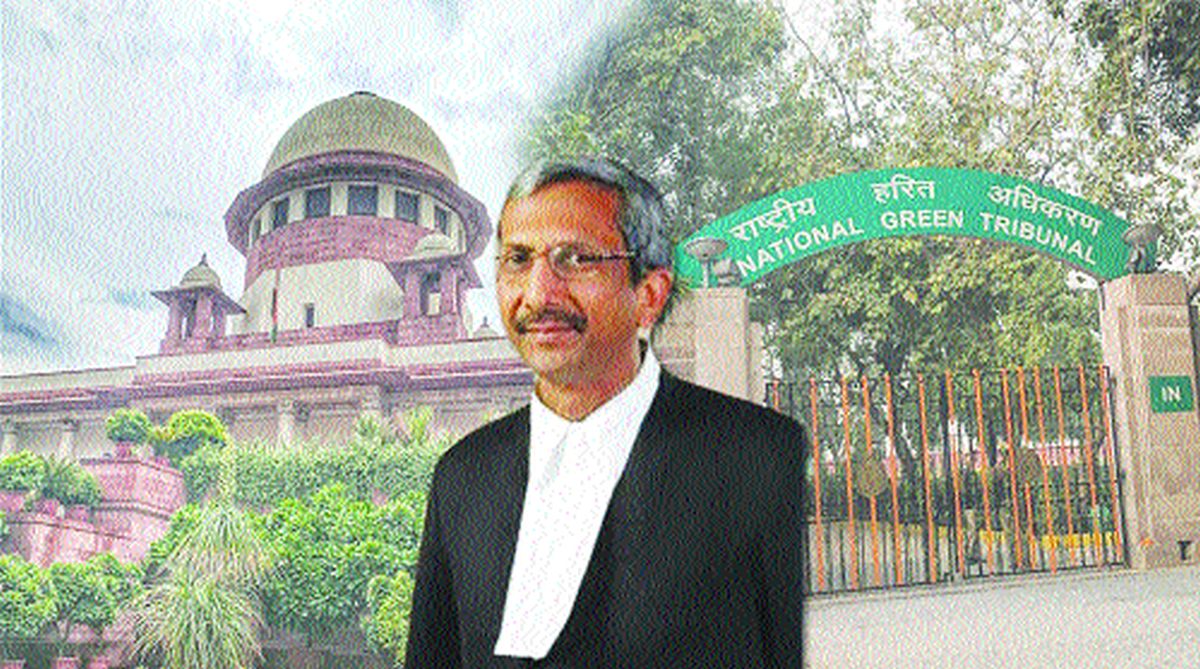

The facts first, as widely reported in the national media. A distinguished judge of the Supreme Court has been appointed the chairman of the National Green Tribunal after his retirement. The Tribunal is charged with the crucial task of checking environmental pollution and thereby promoting green growth, a declared national priority. Such positions need the best talent that the country has.

Such appointments are the exclusive privilege of the Executive and are approved by the Prime Minister as the head of the Appointments Committee of the Cabinet. In other words, it is a Cabinet-level decision in terms of law. Needless to mention, all such appointments are made under the authority and in the name of the President of India, being the highest executive authority in the country.

Enter a Union Minister who is, incidentally, one of the longest serving ministers in the current Council of Ministers. He has publicly opposed this appointment on the ground that the said judge had passed a judgment while he was a member of a Division Bench of the Supreme Court that was not to the liking of the members of the Minister’s caste. Taking a cue from the fulminations of the senior Minister, a junior serving Minister belonging to his caste has similarly jumped into the controversy.

The issue raises a serious question of Constitutional law and propriety. It must be faced head on lest it adversely affect the working of our democracy and the larger issue of the rule of law. It is too serious an issue to be pushed under the carpet or brushed aside as election-eve rhetoric, to be listened to and ignored. It is bound to impact the independence of the Judiciary, now a ‘basic feature’ of the Constitution.

All ministers in the Council of Ministers are supposed to take an oath of office to abide by the Constitution and promote the rule of law. All judgments of the Supreme Court are the law of the land unless reversed in appeal or review. The Union Minister concerned, by publicly criticising the judgment of the Court has struck a blow at the rule of law. That he has, additionally, openly derided a Cabinet decision in the bargain is of lesser moment. As all decisions of the Cabinet are based on the ‘collective responsibility’ principle, he has committed a Constitutional impropriety.

The Minister concerned does not have the alibi of lack of knowledge about the norms of Cabinet functioning or the norms of Constitutional propriety since he has one of the longest tenures as a minister. The judgment has been criticised not on legal merits, as that may have been a mitigating factor, if at all. It has been repeatedly criticised on the ground that it is not acceptable to his caste members. This is a very dangerous stand to take, as the Court’s task is to do justice according to law, not to please this caste or that community.

Undeniably, the Minister concerned, or shall we say the concerned minister has every right, just as any concerned citizen to exercise his Fundamental Right to freedom of speech and expression to criticise a court judgment but strictly on merit. The Supreme Court has itself explicitly recognized this right in a landmark judgment in 1995, in the case of Iyer v. Justice Bhattacharjee. It is now the settled law of the land. It has itself expanded the frontiers of free speech and expression thereby.

The Supreme Court has done a signal service by this judgment. It has balanced the right of an individual to free speech to include the right to criticise any judgment if it is found not conducive to larger public interest. It also arms the Executive to criticise the judiciary if it is perceived as encroaching on the Executive domain. But this right cannot be stretched to assail individual judges. The Court has relied on the prevailing modern jurisprudential norms in civilized democracies, as contained in the comprehensive Halsbury’s Laws of England.

The apex court has, however, entered a very desirable caveat therein. No citizen, let alone a prominent public figure like a serving minister has a right to criticize the conduct of a judge or assail his private views. An informed citizen has a right to criticize a judgment in polite and respectful manner, but not attack an individual judge. What is all the more unfortunate in the present case is that the Minister has overlooked that the Constitution itself imposes an added legal obligation on the Ministers.

All ministers are members of Parliament. The Constitution under Article 121 grants an unfettered right to all members full freedom of speech in the Parliament. Whereas there are restrictions, of course in public interest which can be imposed on the ordinary citizen, to somewhat restrict his right of free speech, there is no such limitation on the Members of Parliament to discuss and debate any issue of public importance.

The Constitution, however, imposes one restraint on the members. They cannot discuss the conduct of any member of the Higher Judiciary. To do so would be contempt of Parliament. By publicly condemning the Judge concerned, the Minister has set a very dangerous precedent. Surely, the minister is not implying that the judiciary should henceforth deliver judgments which are politically correct. The task of the judiciary is to deliver judgments according to law and not to please politicians, even the ruling ones.

There is another danger in the precedent now being created by a ruling minister. If such a conduct on the part of a minister is not checked and visited with at least a public censure by the Executive, it may seriously undermine the independence of the judiciary, a basic feature of the Constitution. In the celebrated case of Keshvanada Bharati, the ‘basic features’ of the Constitution have been termed as “immutable”.

In other words, neither the executive nor the legislature can tinker with the ‘basic structure’ of the Constitution. Or, for that matter even the judiciary. All too often, the term ‘independence of the judiciary’ is invoked, in political discourse. One feels that the full clause should be used, i.e. ‘independence from the executive’, which is more relevant, and educative especially in the Indian context. The danger is ever-present, more through indirect means than through direct ones – witness the stratagem of Judicial Appointments Commission, thankfully aborted by the Supreme Court.

In sum, such an open onslaught on individual judges is unprecedented in any civilized democracy, not to talk of the world’s largest democracy. There is a danger, real and present that such conduct especially on the part of a ruling public figure could seriously undermine judicial independence – individual judges cannot hit back.

The writer is a retired IAS officer and Member, International Academy of Law.