Is India set to become the new beauty destination for global brands?

The Indian beauty market is estimated to reach $2.27 billion by 2028, with a CAGR of 10.91% during the forecast period (2023-2028).

By the power of his mind, Swamiji read his past at first sight and told him everything flawlessly. Goodwin was deeply astonished and impressed.

SNS

“There has been a reign of terror in India for some years. English soldiers are killing our men and outraging our women only to be sent home with passage and pension at our expense. We are in a terrible gloom ~ where is the Lord? … Suppose you simply publish this letter, the law just passed in India will allow the English Government in India to drag me from here (America) to India and kill me without trial.” Alluding to many other similarly hazardous misdeeds of the English government in India, Swamiji wrote this letter (30 October 1899) to an American lady. He made in it a clean breast of his bitter dislike for the British Administration in India. There were also the matters of persecution of the press and journalists, suppression of education, upheaval of 1857 and its aftermath, etc.

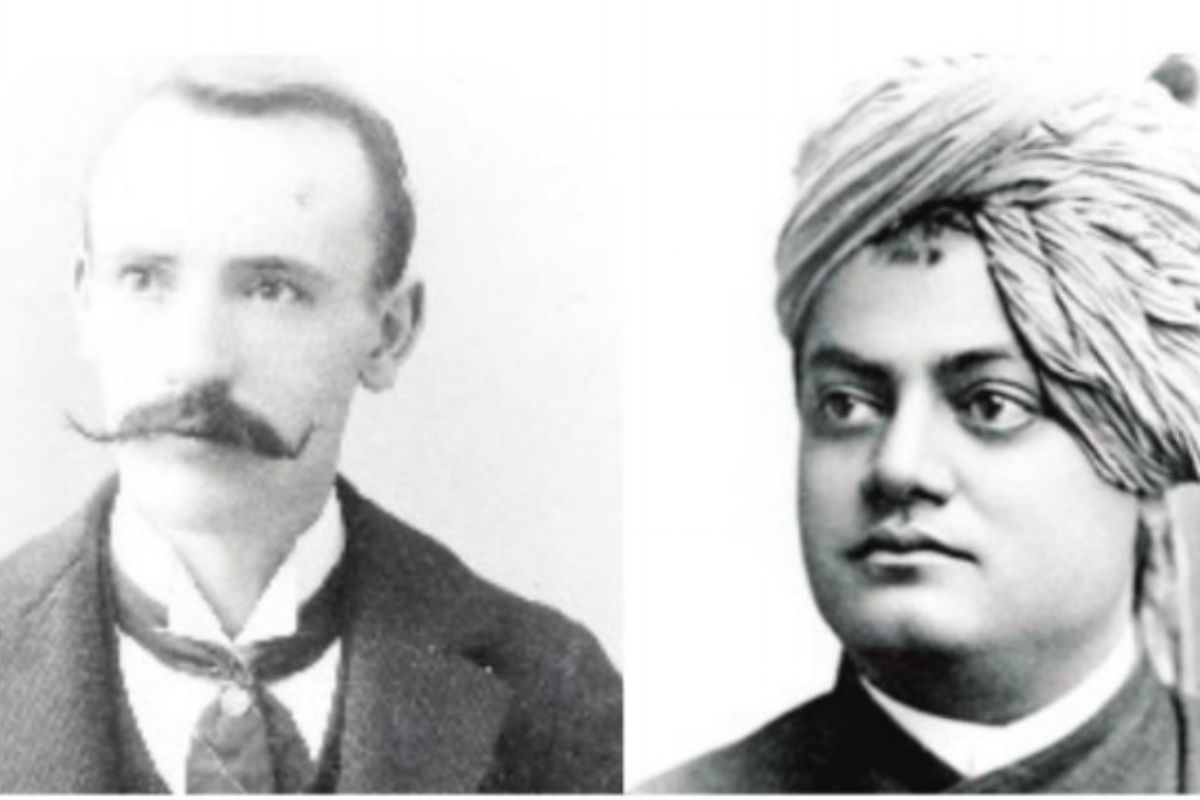

The nineteenth century was thus the zenith of pernicious British rule and its atrocities in India. By any stretch of imagination, it was inconceivable then that an Englishman would ever serve a native, however accomplished, as his Personal Assistant (P.A.). But it had in fact happened in the case of Swami Vivekananda. A young Britisher joined and served him as his stenographer as well as attendant. Not only that, he had left an indelible mark in doing so. He sacrificed himself, playing a vital role in Swamiji’s life and work. After his demise, Swamiji described him with a heavy heart as the first martyr in his cause. Josiah J Goodwin died in harness at Ootacamund on 2 June 1898 when he was hardly thirty-three. He was then working in “Madras Mail”. It was the scourge of typhoid, to which many like him suddenly fell victim and died in the south of the country. Expressing his pain, Swamiji offered condolences on Goodwin’s untimely death in a poem titled Requiescat in Peace (vol IV).

He sent it to his mother with a covering letter. He wrote in that letter: “The debt of gratitude I owe him can never be repaid. …and those who think they have been helped by any thought of mine, ought to know that almost every word was published through the untiring and the most unselfish exertions of Mr. Goodwin. In him I have lost a friend true as steel, a disciple of never-failing devotion, a worker who knew not what tiring was, and the world is less rich by one of those few who are born, as it were, to live only for others.” On 12 December 1895 an insertion was given in a newspaper by Swamiji’s followers in America. They thought Swamiji’s lectures and talks were too precious and they must be taken in short-hand and preserved properly for the future. Before Goodwin, two others came in response and were rejected because of their inability to cope with the speed of Swamiji’s speech. Goodwin was the third to come and he was worth his salt.

Advertisement

He was thirty at the time and full of zeal. Earlier, he was engaged in the job of preparing court reports and had experience of doing editing work in three newspapers for eleven years at his disposal. But, his habits weren’t so good. Gambling spoiled him a lot and had eventually made him utterly penurious. He used to be mostly a loser. Teasing him, Swamiji would tell him, “Your name should have been Badwin, rather than Goodwin.” He loved him dearly, like his son. Goodwin said that he was the son of a poor parent. He had to travel to Australia, Canada, USA and other places in search of earning. He therefore came in contact with many rich people, but received love from none. At last, he was caught in the pure love and sympathy of Swamiji and, as a result, gave up the struggle for earning money altogether. By the power of his mind, Swamiji read his past at first sight and told him everything flawlessly. Goodwin was deeply astonished and impressed.

He instantaneously knew that Swamiji was a spiritual giant. He took refuge in him for the rest of his life. He accepted Swamiji’s discipleship and stopped taking the little remuneration he used to accept. The Midas touch of Swamiji reformed him radically into a thoroughly virtuous person. He said to him in a letter dated 8 August, 1896 from Switzerland: “The road to the Good is the roughest and steepest in the universe. It is a wonder that so many succeed, no wonder that so many fall. Character has to be established through a thousand stumbles.” He became an exceptional example of renunciation and service. Needless to say, Swamiji’s boundless affection was indeed responsible for his quick transformation in that way. He gave him the vows of Brahmacharya and formally included him in the Ramakrishna Order. Hence he served his Guru without any stint from early morning till late in the night. He completely submerged himself in Swamiji’s Vedantic work.

He would attend his prolonged classes in the morning, accompany him on his lectures during the day, and attend his long evening classes. He wouldn’t miss a single word uttered by Swamiji’s lips, transcribed them in shorthand and then finally typed them. The world owes an immense debt to him for his meticulous performance in gathering Swamiji’s immortal lectures which are now available to us in books. Goodwin came to India with Swamiji in 1897. Travelling with him from extreme south to north of India, he witnessed all over India the unprecedented excitement among all and sundry on Swamiji’s triumphant return from the West and left his impressions on record. He collected his lectures everywhere; these were later compiled and published as Lectures from Colombo to Almora. Goodwin was sent to Madras “with the idea of starting a daily paper in English, and also to help Alasinga (one of Swamiji’s most trusted disciples in the South) with the Brahmavadin work”, but, ironically, it was not to be so, because of some compulsions he had to circumstantially face.

On 16 September 1897 he wrote in this regard to another of Swamiji’s trusted disciples abroad, Mrs. Ole Bull: “I have joined the staff of the Mail. They asked me to several times, and as they allow me perfect liberty to make the Swamiji’s work my first interest, and, as, also, it will enable me to keep myself here, and help my mother out, I joined.” Again, on 5 May, 1898 he wrote to Swamiji’s American friend Miss Josepin Macleod from Ootacamund one month before his passing: “I will do anything for him (Swamiji) personally, but I simply do not care a pin for anything else. If I do any of his work, it will be merely because he wishes it. Partly for this reason, I am for the present really out of the work altogether. I also felt that, recognizing as I did that I could do absolutely nothing to help, although I really tried in Madras, it was wrong to remain a burden on him or his, I joined the Mail…” Clearly, he was unhappy that he was away from Swamiji and also for not being able to do anything for him. It was unbearable to him that he didn’t see Swamiji for as long as a period of sixteen months then.

He was missing Swamiji so much. The filial connection between the two was legendary. However, what Goodwin did for Swamiji and thereby for India is unforgettable. Likewise, what Swamiji did by integrating Goodwin in himself as well as in India is a demonstration of the true spirit of India which uniquely teaches us how to offer our bosom to everyone in this world without any discrimination whatsoever. He taught Goodwin a lesson, of which he himself was a living embodiment, and in which he gave a truth for the entire humanity to learn: “It is unswerving love and perfect unselfishness that conquer everything. We Vedantists in every difficulty ought to ask the subjective question, ‘Why do I see that?’ ‘Why can I not conquer this with love?’”

Advertisement