This writer has ventured to make some suggestions to his Muslim friends. Incidentally, his grandfather was a friend of Ahmed Ali Jinnah, younger brother of the founder of Pakistan. The writer himself has struggled with learning Urdu through two educated Muslim teachers. To that extent, he shares an empathy with the Muslims.

He does not mind a Musalman who holds orthodox views and feels that all nonbelievers are kafirs. But then, such a person should undertake a hijrat to a Dar-ul-Islam. It is still conveniently possible to emigrate to Pakistan, Bangladesh and a few other countries, although the choices have shrunk. It would be useful to know the brief background of this problem. After Partition, the Muslims who were left behind in India were understandably apprehensive.

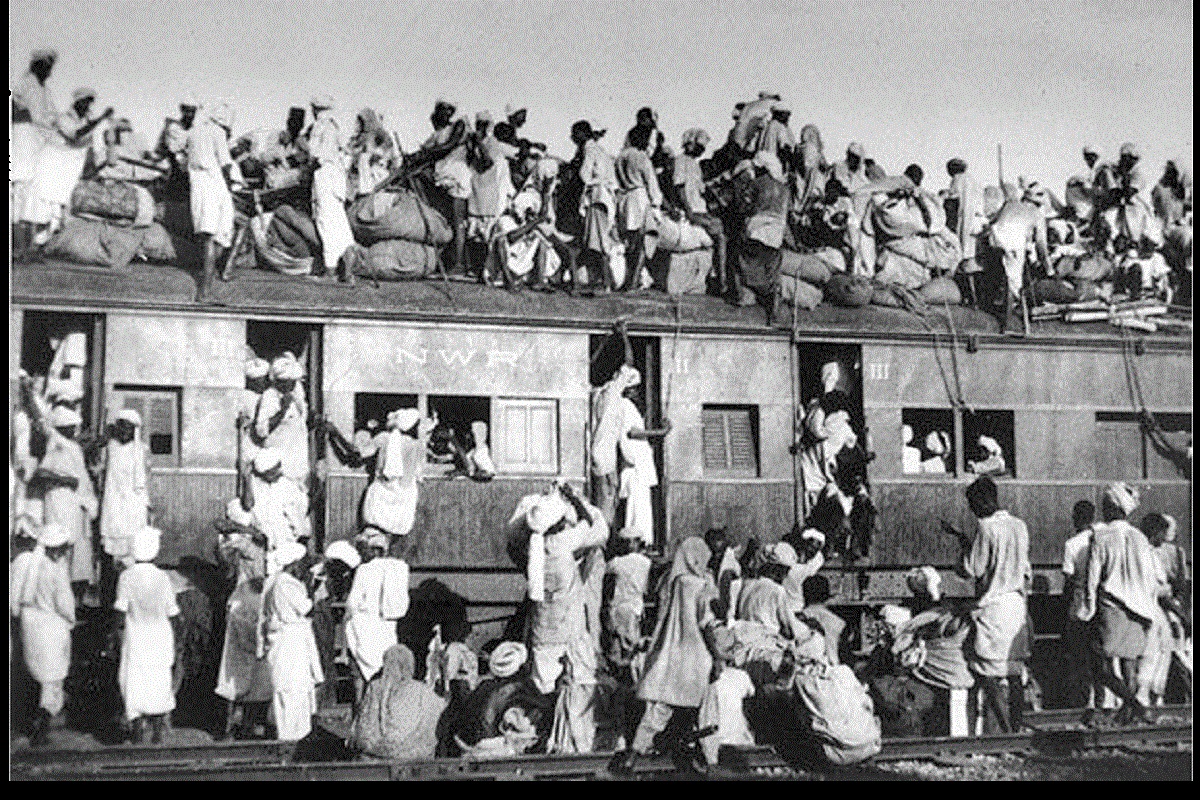

MA Jinnah and seven other senior colleagues had proposed an exchange of population. According to this scheme, the Hindus should do their best to vacate Pakistan whereas the Muslims in Hindustan would leave India for Pakistan. Those unable to move could stay back and in the words of Jinnah, “continue to reside as reciprocal hostages”. Dr. Rajendra Prasad, India’s first President for ten years, in his book India Divided published in 1946, recommended that those minorities who stay back would reside as aliens who are issued visas.

Those who knew these suggestions of the two big leaders became even more apprehensive. Jinnah’s attitude was harsh. He was leaving the Imperial Hotel, Delhi, for the airport to depart for Karachi, in order to deliver his inaugural speech to the Constituent Assembly. The small crowd of leaders who had come to seek his protection were nonplussed by their leader’s words. Jinnah said: “You have done nothing to win Pakistan. I alone have achieved the new country. You will have to fend for yourselves”.

As simple as that. As it happened, Jawaharlal Nehru did not have an adequate support base in the Congress. When in 1946, the party office enquired ,as was the procedure, about electing a new president, 15 Pradesh Congress Committees opted for Sardar Patel, while one PCC chose Acharya JB Kripalani; none voted for Nehru. Yet, Gandhiji insisted on appointing his favourite Nehru through the 21-member Working Committee of the party.

The party president would automatically take over as the Vice-President of the Interim government when it was formed later the same year and then eventually the Prime Minister of India. Nehru’s support base was still missing. The traumatized Muslims left in India were his sitting ducks for acquiring a base. Most of them remained his supporters throughout.

The general impression has been that the Muslims vote almost at 90 per cent and therefore are a valuable base. This was the secret behind the Muslims acquiring and holding until 2014, a veto on Indian policy. Whether overturning through Parliament the Supreme Court granting Shah Bano a deserved alimony because it was against the Sharia, or at the climax, Manmohan Singh, former Prime Minister, declared “Muslims First” and ‘fifteen per cent of the country’s resources to be given to the Muslims first’.

These are but mere examples of the veto. Since 2014, the perception of the Hindus has changed. They feel that ‘enough is enough’. They would now like to enjoy their freedom after these seven decades, without causing inconvenience to anyone else. The Shias have recognized the change in weather and opted out of the Ayodhya fray.

The Sunnis are holding out but to what benefit, only they know. Is it worth waging a tussle for a small piece of land? Do they realize what hurt they cause to the Hindu believers? The question of “whose right was it” was decided on 14 August 1947 when Pakistan was born and its flag fluttered for the first time at Karachi. The only criterion on which British India was divided was religion and no other reason.

Certainly not on territorial grounds as Gandhi told Syama Prasad Mookerjee in the presence of Rajkumari Amrit Kaur in January 1948. Thirty per cent of the land was allotted by the departing British government for 25 per cent of the people which was then the total Muslim population. With a third of the Muslims staying behind, the land allocation to Pakistan was in excess. If an exchange of population had taken place, the demographic picture of India would have been much different. As it happened, West Pakistan drove out nearly all Hindus and Sikhs. Whereas, comparatively very few Muslims emigrated from India.

East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) has over a period of years pushed out three-fourth of its Hindus.Thus Pakistan and Bangladesh have grabbed more than their fair share of the land area. From every angle, the obligation to adjust amicably rests with the Muslims who have stayed back in Hindustan. Just as the Christians, Parsis and Jews lead a congenial life. There are no tensions and certainly no riots.

Whereas Hindu Muslim riots take place somewhere or the other with the regularity of the annual shaddha or the sad fortnight for praying to Hindu ancestors! Gandhi had said at the Round Table Conference in 1931 that such riots are coeval with the British rule. They would cease when the British departed. How many riots have taken place since Independence and how many lives lost? Was he talking baloney?

Or did he not have sense enough to know that before the British, the Muslims ruled in many parts of the country. How could there be riots between the rulers and the ruled? Articles 25 and 30 of the Constitution place the minorities in a superior pdestal whereas the majority community has less rights. Moreover, they contradict Article 14, which guarantees equality before the law to all citizens of India.

They also directly negate Article 15, which is meant to ensure all citizens against discrimination, whether in matters of religion or any other. Articles 25 to 30, therefore, need to be abrogated. India would have been a rather different country had it not been saddled with a 50-year rule by Aurangzeb in the 17th century.

There would have been no temple desecration, no reintroduction of the jaziya tax and other forms of oppression against the Hindus. As a contrast, had Shah Jahan’s eldest son, Dara Shukoh, become the emperor instead of Aurangzeb, India would probably not have been divided into Hindustan and Pakistan.

(The writer is an author, thinker and a former Member of Parliament)