Obamas to produce adaptation of book on Trump presidency

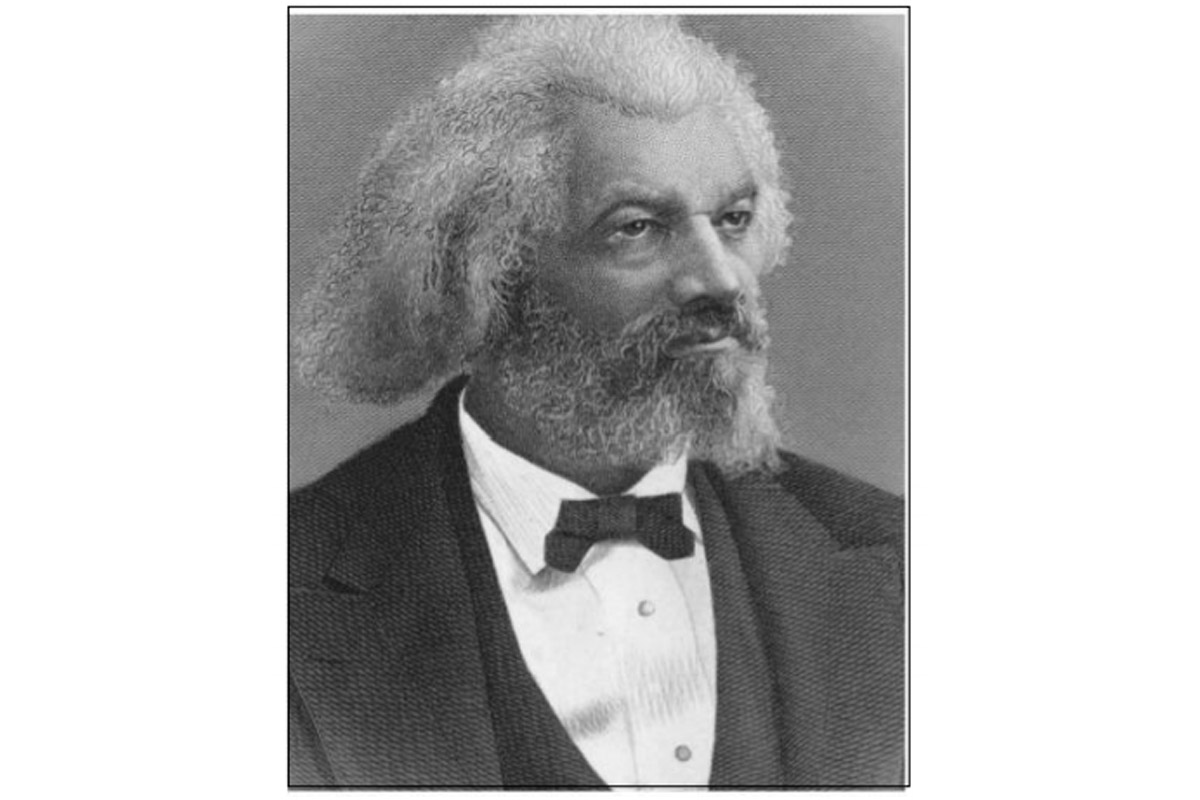

The Obamas' other projects include a biopic on American reformer Frederick Douglass and a period drama set in the fashion world penned by Callie Khouri.

The Bible provided Douglass the ultimate weapon to humiliate and shame White Christians. He would frequently cite passages from the Bible, pointing out their hypocrisy in thanking God for America’s freedom while keeping slaves in bondage in the name of Jesus

It is difficult to imagine a more remarkable life of determination, courage, crusading spirit and success than that of Frederick Douglass, who reached the pinnacle of glory from the lowest depths of a life of slavery. Douglass, who was self taught, rose to become not only the foremost opponent of slavery and one of the most insightful intellectuals of the 19th century, but he was also regarded as an orator of unparalleled stature and a world-class writer.

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland in 1818. He was separated at a very young age from his mother, who was a slave, and was raised by his grandparents. He didn’t know the real identity of his white father who, according to Douglass’s biographers, was his owner. He searched his whole life for the name of his true father without any success.

When he was a young boy, Douglass witnessed the most gruesome murders and violent whippings of slaves by their masters with the help of the overseers. Children were also subjected to merciless whippings. Douglass has written about these brutalities in his autobiography and how it left an indelible impression on the young man’s mind. So, at a very young age, Douglass was initiated into a world that was marked by barbarities, the absence of morals and grave injustices. These tragic and horrific incidents certainly had a profound influence in shaping Douglass’s political views about slavery.

Advertisement

As a young boy, Douglass was extraordinarily bright and very observant. He impressed people around him not only with his razor-sharp intelligence but also with his strong curiosity. It was this curiosity and intellectual persistence that drove Douglass to ask profound questions about issues concerning the origins and ethical and moral dimensions of slavery. Douglass was also known for his prodigious memory, which helped him in important ways when he wrote books about his life.

When Douglass was eight years old, his owner sent him to Baltimore to live as a house servant with the family of Hugh Auld. Hugh’s wife, Sofia, who defied a ban on teaching slaves to read and write, taught Douglass the alphabet. Hugh flew into a rage when he found out what Sofia was doing and forbade her to offer more lessons to Douglass. When Sofia refused to teach Douglass, he was able to get his education from the white immigrant boys in the Baltimore neighbourhood.

Douglass wrote in his autobiography that he used to bribe the neighbourhood boys with the bread that Sophia had provided for him in order to receive help with his spelling lessons. Very often Douglass and these immigrant white boys would be engaged in animated discussions as to why Douglass was a slave for life while the white boys were free. The boys confided in Douglass that they found slavery to be morally wrong and they gave him hope that he would be free one day.

At the age of 13, Douglass spent the hard-earned money that he had saved from polishing shoes for a copy of The Columbian Orator, an anthology meant for students of elocution. The Columbian Orator included passages from famous speeches about freedom. Douglass acknowledged how impactful The Columbian Orator was in shaping his views about antislavery and the democratization of education, while instilling in him the spirit of the American Revolution and the values of republicanism. It was The Columbian Orator that taught Douglass how to give great speeches, focusing on cadence, pace, tone, language, gesture and posture.

It was during this time that Douglass met Charles Lawson, who became his deepest influence. Lawson filled Douglass’s life with hope and instilled in him a deep and insatiable craving for knowledge from books. Thanks to Lawson, Douglass became very familiar with the scriptures. The Bible played a critically important role in Douglass’s adult life in two ways: First, it gave him spiritual centeredness. And second, it provided him the ultimate weapon to humiliate and shame White Christians. He would frequently cite passages from the Bible, pointing out their hypocrisy in thanking God for the nation’s freedom while keeping slaves in bondage in the name of Jesus.

When Douglass was a teenager, he devoted an enormous amount of time to reading on the art of oratory. He was also busy learning what he called the “art of writing.” In order to be a first-rate writer, he voraciously read the works of literary giants from England and Europe. He also assiduously studied the works of the ancient Greek philosophers as well as Continental philosophers. All this reading ignited a fire within Douglass, broadened his horizons, strengthened his determination to find freedom, and inspired him to share his life story with the world.

In 1838, when Douglass was 20, he made his dramatic escape from slavery by traveling north by train and boat from Baltimore to Philadelphia and then to New York. Two weeks after arriving in New York, Douglass married Anna Murray, a free black woman whom he had met in Baltimore. After marriage Douglass settled in Bedford, Massachusetts, where he was working on the dock. During this time, he was giving anti-slavery speeches in his community, which gave him some prominence.

In 1841, Douglass was invited to speak about his experience as a slave at the antislavery convention in Nantucket, Massachusetts. His extemporaneous speech was so riveting, impactful and memorable that he was immediately catapulted to the distinguished role of the speaker for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. His lectures, which were filled with passion, erudition and richness of voice enthralled his audiences everywhere, establishing Douglass as the key spokesperson of the antislavery movement. In May 1845, Douglass wrote his autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which became a classic in American literature and was a phenomenal success worldwide. Douglass’s autobiography served as the most important source of information for slavery from a slave’s viewpoint. Douglass later wrote two more autobiographies, which were works of political and social criticism with the purpose of abolishing slavery in the United States and for granting full rights and privileges to Blacks. For Douglass, who had already gained worldwide fame as a writer and orator, these two autobiographies permanently secured his position in the pantheon of great literary giants.

On 5 July 1852, Douglass gave a speech titled “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” at an event commemorating the signing of the Declaration of Independence at the Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York. Although Douglas gave this speech more than 160 years ago, it is regarded as one of the greatest speeches in the annals of history. According to David Blight, author of the 2019 Pulitzer Prize winning biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, “in both secular and sacred terms, prescient in its vision and powerful in its unforgettable language, Douglass had delivered one of the greatest speeches of American history. He had transcended his audience as well as Corinthian Hall, into a realm inhabited by great art that would last long after he and this history were gone.”

During his long and celebrated life, Douglass held many highly distinguished positions in the US Government. During the US Civil War, Douglass was appointed as a consultant to President Abraham Lincoln, advising him on matters of utmost importance. Their relationship became so close that at his second Inauguration, President Lincoln greeted Douglass at the White House reception not as “Mr Douglass” but as “my friend.” Throughout his life, Douglass not only fought for full civil rights for freed slaves, but he also vigorously supported the women’s rights movement.

Douglass died at the age of 77 after living an astonishing life. He led a movement in New York to desegregate schools before there was a civil rights movement. His tireless voice helped lay the groundwork for the emancipation of slaves and for the 15th Amendment, giving the Blacks in the United States the right to vote. In his essay in The New Yorker, “The Prophetic Pragmatism of Frederick Douglass,” Adam Gopnik sums up Douglass’s accomplishments thus: “In his legacy as prophetic radical and political pragmatist, in the almost unimaginable bravery of his early journey and the resilience of his later career, in his achievements as a writer, activist, crusader, intellectual, father, and man, the claim that he was the greatest figure that America has ever produced seems hard to challenge.”

I have provided a quick glimpse of the life of Frederick Douglass due to limitations of space. I am fully aware that my piece falls short of capturing the many facets of this great man’s life who often has been called the greatest American of the 19th century. I therefore ask for the reader’s indulgence.

The writer is professor emeritus of communication studies at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles

Advertisement