Nelson Mandela’s birth anniversary celebrated at Springdales School

Springdales School celebrates Nelson Mandela's birth anniversary, honoring his remarkable 67 years of community service.

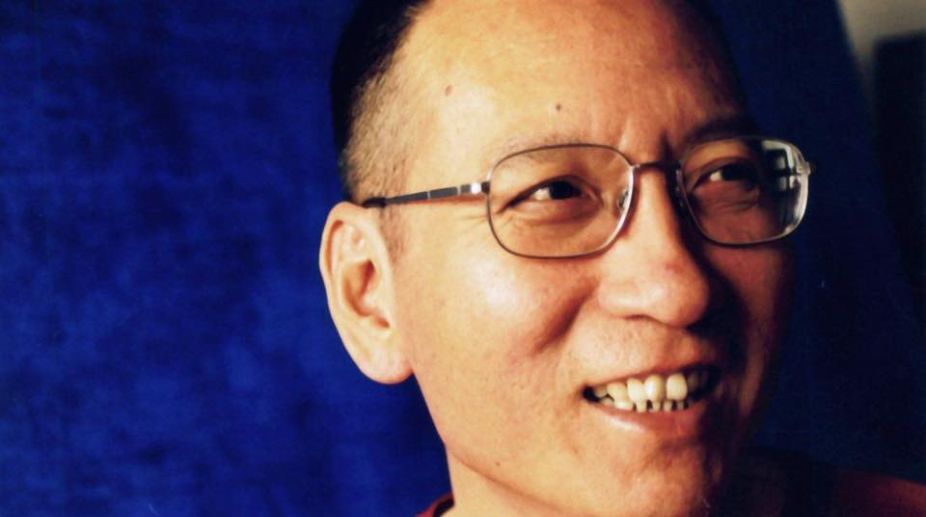

Liu Xiaobo (Photo: Facebook)

After Nelson Mandela, the most famous prisoner of conscience of our time, Liu Xiaobo, died on 13 July. Sentenced to 11 years in jail in 2009 for “inciting subversion of state power” and treated as a common criminal, Liu’s end came after a long ordeal in the Chinese dungeons with no one, not even his wife who was also under house arrest since 2010, being allowed to stand by him during his lonely fight with liver cancer until the very end.

The Economist has rightly described him as “one of the global giants of moral dissent”. It has compared his release from prison with that of Carl von Ossietzky, the only other Nobel Laureate to have been released from prison… only to die. Ossietzky was awarded the prize in 1935 while in a Nazi concentration camp, and succumbed to consumption upon release.

The gruesomeness of the parallels cannot be missed, because both regimes believed in silencing the voices of their people and stifling dissent by applying the most ruthless repression.

Advertisement

It was not known how late Liu’s cancer was diagnosed or why he could not be sent to the hospital for treatment until a week before death.

The State never allowed him to go abroad for treatment; instead it deployed a platoon of guards around his hospital bed and an army of internet censors to wipe out any reference to him, doing everything in its power to erase his existence out of public memory.

Liu’s case became a cause celebre ~ symbol of a struggle ~ because of his stature, but there are thousands of prisoners rotting in the hell of Chinese jails just because they hold a view that their rulers disapprove of, demanding freedom to speak against the merciless oppression by the state machinery, the endemic corruption in the higher echelons, and the inhuman suppression of people of different ethnicities in Tibet or Xinxiang, who according to the Chinese government are all counterrevolutionaries.

Their numbers are anybody’s guess, as hard information rarely slips through the iron curtain erected by the Chinese censors. But the scale of their surveillance can be measured from the fact that not a single message of condolence had slipped into the public domain from any of the 700 million users of the social media in China. Not one dared to express any sign of sympathy for what Liu stood for; or if anyone did, it was not allowed to escape the ever so watchful eyes of the censors.

The State ensured that his death remained a non-event, and no memorial would ever come up to stand as a symbol of eternal defiance against tyranny and dictatorship.

Even the responses of the Western democracies, otherwise loud in protestations against the suppression of human rights elsewhere, were unusually muted.

A Chinese foreign ministry spokesman warned that no country has the right to interfere in what he claimed was China’s internal affair. Not one voice was heard loud enough to shake China’s conscience.

The censors may raise a toast to their success ~ July 13, 2017, in all likelihood, will remain as anonymous as June 4, 1989, except in the hearts of worshippers of freedom and democracy, hidden from the dictator’s prying eyes.

Yet Liu did not rise in armed revolt against the might of the State. Nor for that matter did he plan any upheaval to challenge its unbridled power over people’s lives.

He even criticised the Chinese dissidents who migrated to the West, incurring their wrath. During the Tiananmen Square upheaval, he had returned from a fellowship in Columbia to take part in the historic movement.

He was on hunger-strike along with three other dissidents and persuaded many of the occupying students to withdraw, who otherwise would probably have been killed, and suffered incarceration for 19 months, emerging from it ever stronger in faith and hope for an oppression-free, democratic China. In 2008, the last time he was incarcerated, he had merely petitioned people to sign for democracy.

When he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, while still in prison, for being the “foremost symbol” of the struggle for human rights in China, it was only expected that he would not be allowed to go to Norway to receive the prize.

Rather, as would befit the rulers of a totalitarian regime, pulling its economic might and flexing its military muscle, China forced as many as 19 timid countries to boycott the award ceremony, and downgraded its diplomatic relations with Norway. An empty chair received Liu’s Nobel Prize.

A speech he had prepared to deliver during his trial in 2009 which was disallowed by the judge, was translated and delivered on that occasion.

In that speech he said, “Merely for publishing different political views and taking part in a peaceful democracy movement, a teacher lost his lectern, a writer lost his right to publish, and a public intellectual lost the opportunity to give talks publicly. Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth. To strangle freedom of speech is to trample on human rights, stifle humanity, and suppress truth.”

“No one can bar the road to truth, and to advance its cause, I am prepared to accept even death”, another dissident Nobel Laureate, Alexaner Solzhenitsyn, wrote in the preface to his autobiographical novel Cancer Ward that symbolised the malignancy that would end in the death of the Soviet Union.

Both cancer and the concentration camp condemn the victim. While cancer only destroys the body, the camp dehumanises him before decimating and destroying his soul. Liu didn’t allow his soul to be destroyed, and his humanity to be substituted by hatred and fear. “I have no enemies and no hatred,” he said during his trial in 2009.

In Cancer Ward, Solzhenitsyn wrote, “Sometimes I feel quite distinctly that what is inside me is not all of me. There is something else, sublime, quite indestructible, some tiny fragment of the Universal spirit.” Liu’s faith and love, against the face of repression, were indestructible.

The truth of Chinese repression cannot indeed be hidden away or overlooked, and there have been and would be many more like Liu to die “unwept, unhonoured and unsung”. He spent 13 of his last 28 years in prison, moving in and out of it.

In 2008, he was imprisoned just two days before the release of the so-called “Charter of 08”, which replicated Charter 77, the appeal issued by dissidents in Soviet-era Czechoslovakia in 1977, demanding an end to oneparty rule, democracy and human rights. Charter 08 was signed by hundreds of people. That was some time after he had urged the Chinese Government to talk to Dalai Lama in the wake of severe unrest in Tibet, angering the communist leadership beyond measure.

“We stand today as the only country among the major nations that remains mired in authoritarian politics. This must change… The democratisation of Chinese politics can be put off no longer”, he demanded in the Manifesto of Charter 08. In his Nobel speech, Liu had said, “I hope I will be the last victim of China’s long record of treating words as crimes.” Though it seems extremely unlikely, the hope may not be altogether ill-placed. Night is the darkest before dawn, and as Minxin Pei, author of China's Crony Capitalism, has pointed out, China’s economic miracle seems to have almost run its course and when economic growth starts faltering, an authoritarian state turns to ruthless repression and appeals to nationalism to hold onto power.

The regime’s mistreatment of Liu was actually a sign of its weakness, insecurity, and fear, not of strength. It was heartrending to watch his wife, Liu Xia receiving Liu’s ashes after his cremation in the presence of State officials. Liu’s Nobel speech was equally touching; it reflected his love for his wife he could not spend enough time with ~ “I am serving my sentence in a tangible prison, while you wait in the intangible prison of the heart.

Your love is the sunlight that leaps over high walls and penetrates the iron bars of my prison window, stroking every inch of my skin, warming every cell of my body, allowing me to always keep peace, openness, and brightness in my heart, and filling every minute of my time in prison with meaning.

“I am an insensate stone in the wilderness, whipped by fierce wind and torrential rain, so cold that no one dares touch me. Even if I were crushed into powder, I would still use my ashes to embrace you.” Xia has to live her life now with those ashes, and his memory.

(The writer is a commentator. The views expressed are personal)

Advertisement