Occupying a mere eight per cent of the total land area in India, the seven Northeastern states and its ethnically-diverse people is a “micro-community” within the country. The anonymity of belonging to a geographical region is itself challenging, as there is no common Northeastern Indian identity. Culturally and ethnically distinctive larger identities such as Nagas, Meiteis, Axomiyas alongside Kuki, Mizo, Khasi, Garo and many other ethnic and non-ethnic communities, including Bengalee Hindus and Muslims comprise a significant diversity that is “largely mismanaged”. The issue is how to manage this diversity at the national level?

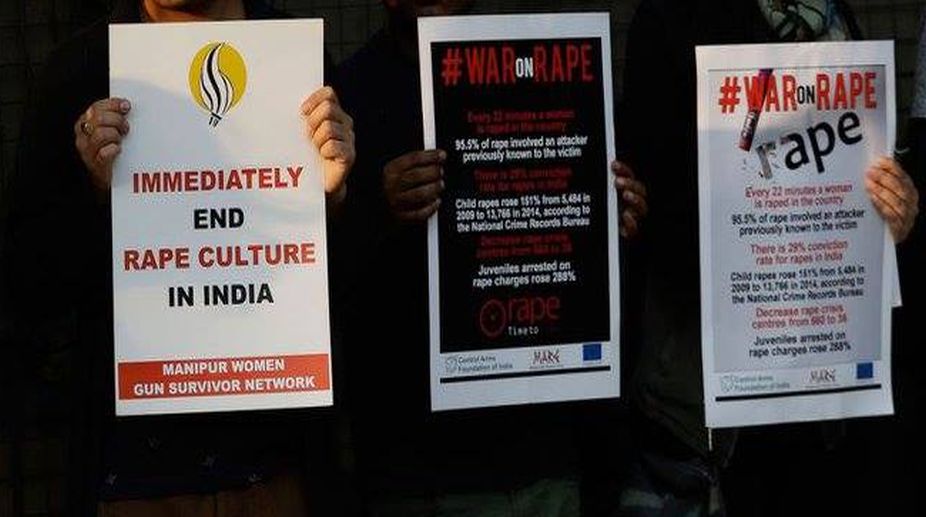

Continuous harassment, humiliation and repression in the form of racism, under-representation, misrepresentation, as many scholars have suggested, goes on unabated. Chilling videos of landlords beating up Northeast girls in January in Bengaluru, the rape of another in Delhi’s Green Park area, rescue of young adult girls from traffickers’ network are some of the common malaise faced by an ordinary Northeasterner, as they travel to other parts of the country.

In the late 1960s, Nari Rustomji termed Northeast India as a “Mongoloid fringe” of the country. Colonial rulers drew lines, Inner and Outer, and reinforced them with unenviable pusillanimity and controlled movement outside the hills. Post-colonial regimes in India continued with either a “leave them alone” or “mainstreaming”, leaving a lot of loopholes in ensuring genuine recognition of cultural and ethnic specificity across the country.

The politics of misrepresentation went to the extent that in the popular biopic blockbuster Mary Kom, Priyanka Chopra replaced a Meitei actress Bala Hizam or another tribal actress Masochon V Zimik, who did not have the needed prosthetic eyelid that Chopra had to put on to make her look like Mary Kom. It is a complex substitution of a wide eyed Punjabi to turn her into chinki-eyed Mary Kom. This incident highlights how Northeasterners cannot represent themselves without a sanction from dominant identities.

In various media discourses too, Northeasterners are presented in terms of conflict, violence, insurgency, meat-eating and other such stereotypes. Within regional media, hill districts and remote localities are never talked about except in a negative way of presenting violence, insurgency or any other disruptive issues. Hill tribes of Manipur face exclusion, discrimination and arbitrary difference that makes them realise their experience of being treated unfairly.

A recent work of a non-fiction by Nandita Haksar, entitled The Exodus is Not Over: Migrations from the Ruptured Homelands of North-east India brought out how Tangkhul women face everything — death to rape and sexist exploitation in Goa and Delhi. A large number of malls in Delhi, Haryana and Punjab, which employ people from the Northeast portray a similar story of a culturally different migrant workforce that have to often bear the brunt of being different-looking with very different food habits. The upmarket restaurants, malls and markets make use of their language skills and other positive features, while they keep facing a discriminatory looking-down by owners, customers and buffs, although there are instances of fellow-feeling and kindness.

What is at issue is the very idea of an Indian face as distinguished from a Mongoloid face along with all its attendant cultural stereotypes, which create a sense of alienation and otherness. For the Northeasterners inventing new forms of socialisation is a constant need to link themselves with “strangers” as employers and neighbours in Indian cities, which is a major challenge. They remain as intruders in other social space of being Indian, as “pastoral keepers” of cultural norms in cities may not give them the connective tissue.

Lin Laishram, who acted alongwith Priyanka Chopra in Mary Kom stated that in every audition she had to face discrimination. Atim, the chief protagonist in Nandita Haksar’s work sees “some of her Tangkhul workers go out with managers” to get some favour, while she experienced statements like “no job for chinkies” here. Do the ideas of India fail to accommodate the racially-different? As professor Bimol Akoijam, a clinical analyst stated, it is like “when this ‘racial other’ is positioned as ‘backward’ or ‘tribal’ (anthropological subjects), it produces a judgment that converts the ‘difference’ to being ‘inferior’. This informs the racist attitude towards the people from India’s North-east”.

Akoijam went onto pointing out the need for sensitivity about racism as Article 15 of the Constitution debars discrimination on the basis of sex, community, religion and race. He also pointed out, albeit for the first time, that race emerges as the major category of discrimination in the context of Northeasterners coming to live in mainland India.

Indeed, he had the shock of his life when he found a reference in JD(U) Rajya Sabha member Pavan Varma’s book Becoming Indian as “my African friend”. Akoijam sought a correction as he hailed from Manipur, but the author never thought it fit to correct it. Thanks to the racist analogies of misrepresentation, Northeasterners could be anything but Indian, they could be Chinese, Nepalis, Africans and the like.

In matters of food too, for instance, a broccoli is never a part of Assamese cuisine nor is fermented bamboo to Jats. To bring it even closer, akhuni (soya bean) is not central to most cuisines found in Assam but certainly to the Meiteis and Nagas. Our mental map of landscapes is also imagined through food. Any attempt at exclusion and intolerance towards practice of those elementary cultural practices is a gross violation of human rights and secular understanding of Indian society. A major problematique in this is eating of beef, pork, insect, or dog meat by North-easterners and hill people, which is culturally prohibited.

One remembers Naga supremo Angami Zapu Phizo shouting at the Governor of Assam on the occasion of the signing of the 1975 peace accord in Shillong. Phizo remarked, “How can there be peace when one side does not share the food of the other side?”

It is seen at large that the food culture of Indian people are divided on multitude of connotations—value systems, religious beliefs and caste associations. Different kinds of food cultures and habits exist parallely, however, it necessarily doesn’t mean an existence without any conflict. As such ecological and social niches that food from North-east carries is taken with a sense of being exotic. But certainly, it does not constitute as an essential part of Indian food culture of samosa or jeelabi or sabjee.

Students from the Northeast living in Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, and also in other metros, often share a very conflicting relationship with their landlords and neighbours. They often face complains of their food being smelly and stinky. One sees very evidently that food has become an instrument of creating a distinctive other and can often cross that already ambiguous relationship to become violent.

Although public memory is short, one would recall the exodus of Northeasterners from major cities in India. This was in 2012 when violence broke out in Bodoland forcing thousands to leave their homes and hearths. It almost turned communal where people were killing each other or burning houses—about 77 people lost their lives and 400,000 had to take shelter in relief camps. Even after five years, at least half of them continue to stay put. To this violence, some hate-rumours were spread through social media that people from the mainland were targeted in the Northeast. This led to attacks by some unknown people in various metros in India, triggering panic among students and others who belong to the North-east. The attacks were in retaliation to the displacement in Bodoland. An estimated 200,000 from various cities returned home. This resulted in restaurants running out of staff, malls with no security guards, airlines and airports with fewer crew members and so on.

This targeting of the people in the cities was the result of bad understanding of geography and it carried strong racial undertones. It was a situation where anyone who looks like a Northeasterner was thought to be a Bodo. If that is not racism and bad geography, what is it? This is the result of absence of the Northeast subject from school textbooks in the mainland. Although, some efforts have been made recently, the Northeast largely remains neglected in school textbooks. Is this not internal orientalism?

The imagination of the Northeast in the minds of most Indians is one of an unknown territory, whose inhabitants are not much known. They are known only if they accept mainstream culture such as Hinduism (in case of Meitei or some Arunachalee tribes) and along with the package, a mainstream language like Hindi. Certainly one does not see an easy way out of the situation.

The mp Bezbaruah Committee that recommended several cultural, legal and administrative measures to end discrimination of Northeast people in Delhi and other cities, could not address and recognise the question of race, which seemingly arises over and over again in this saga of difference.

(Prasenjit Biswas is an Associate Professor at the Department of Philosophy, NEHU, Shillong and Suraj Gogoi is a researcher in Sociology, National University of Singapore)