Academy overhauls rules for 2025 Oscars

Hollywood's Oscars set for a revamp in 2025 with new rules and categories for films, composers, and more. Details inside.

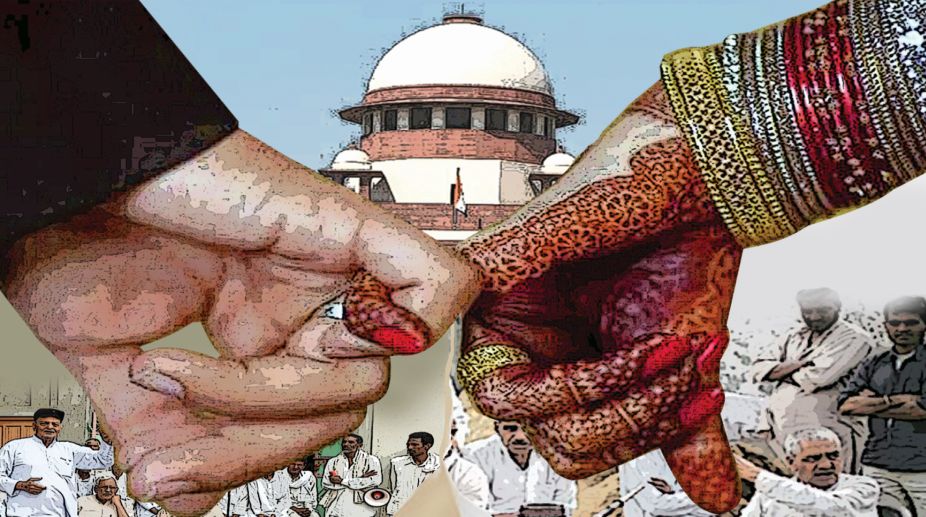

Supreme court

Claiming Constitutional rights in the personal sphere has undergone a sea change since the pronouncement of the ‘Right to Privacy’ judgment by the Supreme Court vide Justice K. S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) & Ors vs Union of India & Ors. Several forms of rights enjoyed by the citizens of India in private life covering all kinds of personal relationships are now protected against State exigencies through this judgment.

One of the most commonly enjoyed rights in our private lives is the ‘right to marry’ with choice. An individual’s freedom to marry especially in case of two consenting adults is now a right subsumed in the mandate of privacy law evolved by the Supreme Court. Whether the privacy judgment will lead to a cultural revolution within communities, faiths and society as a whole is a larger question of social debate. As of now, in the post privacy judgment phase, its judicial application to the petitions challenging an individual’s freedom to marry by his or her choice is explored here.

Social governance of marriage

Advertisement

Generally, the entire discourse on marriage and decision of marriage in our society is largely based on social recognition and governed by societal norms. Social governance of marriage from right to marry till its survival or dissolution has been greatly influenced from caste, class and religious practices.

Marriages are also generally susceptible to hundreds of social views. Majority of these opinions are social judgments vis-à-vis marriage, passed by the range of stakeholders including parents, relatives, friends, and so-called custodians of religion (priests, irrespective of religion).

At the receiving end of such value judgments are inter-caste and inter-faith marriages. They have been the most vulnerable kind of social relationships and often subjected to social challenge and wide public scrutiny. And when solemnised without concurrence of parents, such marriages have to withstand community anger, social outrage and social strictures against the couples. In a way such inter-caste and inter-faith marriages are virtually declared as blasphemous.

Notwithstanding such social implications of inter-caste and inter-faith marriages, we have always had personal laws governing the legality of marriage including prescribed grounds for divorce, settlement of alimony and child custody. However, never before have couples in Indian society begun to claim Constitutional protection for their marriage as today. An era is almost over when right to marry was viewed strictly from a social perspective.

With the ‘Right to Privacy’ judgment in place, it seems to have created scope for a generational shift. Two recent high-voltage cases of inter-caste and inter-faith marriage, post the privacy judgment, bespeak a trend of social change. Both are still sub-judice but the interim courtroom progress reflects a visible change even in the judiciary’s way of handling such matters.

Not susceptible to State investigation

First is the case of Shafin Jahan vs Union of India in which the Supreme Court’s approach as reported after the hearing on 23 January 2018 has been to squarely differentiate between the so dubbed issue of ‘love jihad’ and the right to marry. The Apex Court has apparently paved a way for the privacy right concerning marriage to win over the ‘love jihad’ case which was originally made out. This is why the court told the National Investigation Agency (NIA) that it could probe anything other than marital status.

A balance has thus been struck to prevent State’s intervention in the legitimacy of the marriage per se. At the same time, the Apex Court didn’t prohibit NIA from continuing its investigation concerning ‘love jihad’ angle as part of its mandate and jurisdiction.

In fact, this can be seen as a classic example in recent times, where the Supreme Court has justifiably invoked its powers of limiting State action from breaching the Constitutional right of privacy on one hand and with equal ease restrained itself from being caught in the judicial overreach debate by not touching upon the general investigative powers of NIA concerning other aspects of this case. Equilibrium has thus been delicately created by the Supreme Court between the enjoyment of Fundamental Right to privacy and State’s power and jurisdiction of criminal investigation.

None can interfere

The judiciary has increasingly begun to view marital cases in a special way under the scanner of right to privacy. The courtroom deliberations in the case of Shakti Vahini vs Union of India, W.P. (C) 231/ 2010 which came up for hearing on 16 February 2018 echo the non-interventionist judicial approach towards a marriage solemnised between two consenting adults.

It is seen that couples marrying out of love especially within a similar gotra are usually not easily accepted in some parts of the country, particularly in Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. A private body called the ‘Khap Panchayat’ usually assumes the role of a local court and questions the legality and sanctity of such marriages. In their self-assumed role as custodians of culture, bodies like ‘Khap Panchayats’ go to the extent of harassing couples and also subjecting them to physical harm. It is also reported that in some cases, such couples are brutally killed by the private armies of ‘Khap Panchayats’.

In such cases, it is quite clear that the Hindu Marriage Act would take care of the permissibility of marriage by virtue of the legal provisions. The courts are also well empowered to scrutinise such marital relationships if challenged in the court of law.

Therefore, the need of social supervision and especially moral policing by a few members of society does not arise. On the contrary, in the name of protecting tradition and culture such organisations or groups torture and harm consenting adults who marry by choice. The Supreme Court took a clear stand on this issue. It squarely placed the marriage by two consenting adults including marriages without parental concurrence, within the larger domain of ‘right to privacy’.

The Supreme Court clarified that no one from society including the parents or relatives of the couple can interfere in the marriage by two consenting adults. Organisations like ‘Khap Panchayat’ have no business to assume the role of an adjudicatory body and decide the permissibility of such marriages.

Such matters are clearly an integral part of an individual’s freedom. It has already been established now that the liberty of having a family life, marriage, procreation and sexual orientation are all integral to the dignity of the individual. Above all, the privacy of the individual recognises an inviolable right to determine how freedom shall be exercised.

Creative Constitutional Interpretation

Judiciary has over time explored creative ways of Constitutional interpretation by digging deep into the Constitutional text and the Constitutional Assembly Debates. This has always enabled the courts to expand the horizons of Constitutional rights to bring them closer to their true intent and purpose.

Post the privacy judgment, the cases concerning inter-caste and inter-faith marriages have provided occasions for the Supreme Court to limit State interference in an individual’s enjoyment of right to privacy wherever justifiable.

When considered rationally such judicial creativity surely offers some respite to the victims of caste and religious attacks for enjoying their marital relationship outside caste and faith and especially without parental concurrence. At least a uniform legal application now stands well defined in treating marriages of two consenting adults of diverse faiths and communities alike, within the Constitutional spirit of the right to privacy.

The lines have nevertheless been drawn for good by the Supreme Court that on the one hand the State cannot question the marital status of two consenting adults and on the other hand, parents or community cannot interfere in the right to marry with choice of an individual.

With such judicious activism, let us hope our society will take a giant step forward in the 21st century because the highest court of the land has now debugged the blurred interpretation of Constitutional text and prevalent legal myth concerning the privacy aspects of the right to marry. Marriage is therefore an exclusively private affair and doesn’t attract any State or social interference.

The writer is Assistant Registrar (Research), Supreme Court of India and Assistant Professor of Law, National Law University Odisha, Cuttack.

Advertisement