Climate costs

As the relentless march of climate change continues to reshape our world, the looming threat to residential property is becoming increasingly apparent.

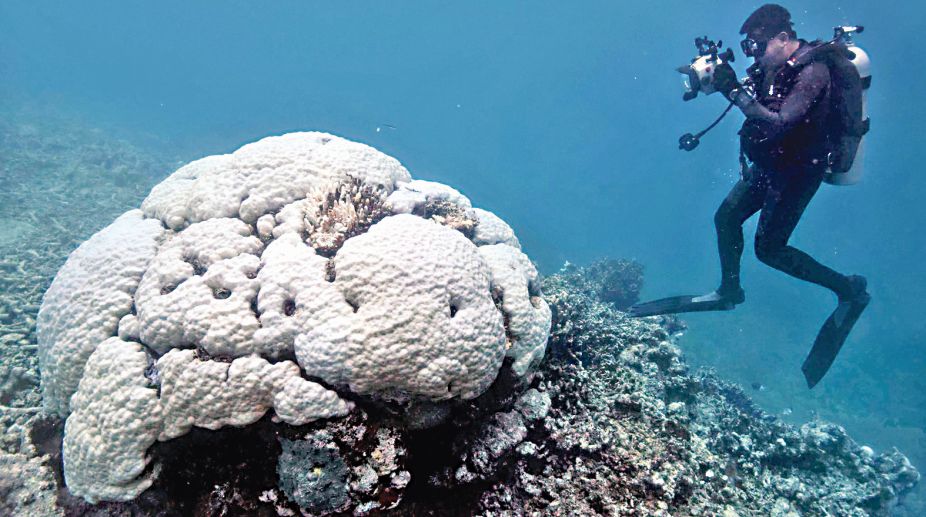

A coral affected by the ‘white syndrome’

Plastic trapped in reefs around the world is having a serious impact on coral health, according to a new study. More than 11 billion pieces of plastic were lodged in the Asia-Pacific oceans corals, said researchers from New York’s Cornell University who studied them. Such debris appeared to be leading to a greater prevalence of coral diseases, they wrote in their findings, published in the journal Science.

This contact with plastic increases the likelihood of disease striking corals from four per cent to 89 per cent. “Our work shows that plastic pollution is killing corals,” said senior author Drew Harvell, an ecologist at Cornell. It is thought that the increase in disease could be due to plastic items blocking light and oxygen from reaching the corals, which require both to survive.

Depriving them of these could also make corals more susceptible to infection by harmful microbes, known as pathogens. Plastic could also actively transport pathogens into coral reefs. “Plastic debris acts like a marine motor home for microbes,” said Joleah Lamb, a marine biologist at Cornell University and lead author of the new study.

Advertisement

While the link with disease is unknown, past studies have established that plastics provide perfect havens for microbe colonies. “Plastic items — commonly made of polypropylene, such as bottle caps and toothbrushes — have been shown to become heavily inhabited by bacteria. This is associated with the globally devastating group of coral diseases known as white syndromes,” said Lamb.

White syndrome is spread by bacteria, and causes parts of corals to die leaving a white band of dead tissue. “What’s troubling about coral disease is that once the coral tissue loss occurs, it’s not coming back,” said Lamb, “It’s like getting gangrene on your foot and there is nothing you can do to stop it from affecting your whole body.”

The new discovery comes at a time of increased awareness of plastic pollution. The UK Government has said it will make tackling plastic waste a top priority in its environmental policy. This year has already seen a UK ban on the manufacture of products containing tiny fragments of plastic called microbeads, as well as debate over the future of disposable coffee cups and plastic bottles.

By increasing coral’s susceptibility to disease, plastic may contribute to the devastation of the world’s reefs, many of which have already been weakened by a string of climate change-induced bleaching events.

To establish the link between plastic and disease, Lamb and her colleagues examined 159 coral reefs from Indonesia, Australia, Myanmar and Thailand. As well as documenting the plastic waste they saw, the scientists visually examined nearly 125,000 corals, looking for evidence of disease.

They found that when plastic was in contact with coral, the chance that it also showed signs of disease increased by a factor of more than 20 compared to coral that was plastic-free. “We know that plastics are widespread in the ocean, and it’s no surprise to me that corals are encountering them,” said Richard Thompson, a marine biologist at the University of Plymouth, who was not involved in the study.

Thompson added that in his own work he has documented over 700 species encountering plastic debris, and evidence of harm coming to them as a result. “Laboratory studies have shown that plastic encounters can cause really subtle, chronic effects and harm, compromising the ability of organisms to grow in the normal way for example,” he said, “Any compromise like that is going to make creatures more susceptible to the risks of other diseases.”

However, he noted that while plastic could present an extra challenge and may be linked with an increase in disease risk, this study does not show that plastics are carrying pathogens into the reefs. “They do not present clear evidence as to whether the pathogens were transferred by the plastic — but that is certainly a possibility,” he said.

Whatever the mechanism by which plastic is impacting coral health, the researchers want their work to inform efforts to protect the world’s reefs. “Our goal is to focus less on measuring things dying and more on finding solutions,” said Harvell, “While we can’t stop the huge impact of global warming on coral health in the short term, this new work should drive policy towards reducing plastic pollution.”

The independent

Advertisement