Barrackpore railway station turns into canvas before the festival of colours

The initiative has been taken by the Eastern Railway aiming to elevate the aesthetics of the suburban town nestled along the banks of the Hooghly River.

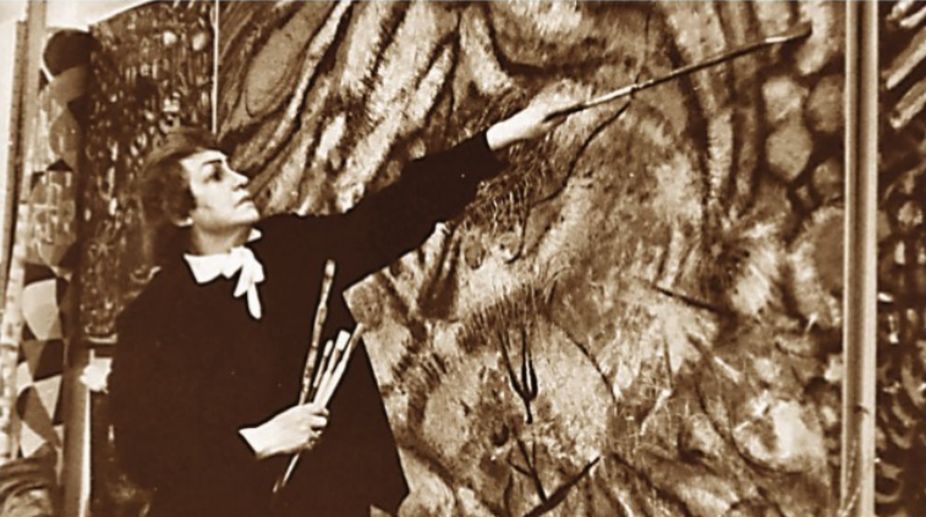

This is the first UK retrospective of Fahrelnissa Zeid, one of a series of Tate exhibitions exploring overlooked or forgotten artists, many of them women, and part of an admirable effort to look outside the usual European-American art historical cannon. A process that began earlier in the decade when the Tate held retrospectives for Lebanese painter Saloua Raouda Choucair and Sudanese artist Ibrahim El Salahi.

Zeid, born in Istanbul, Turkey, in 1901, had a brutal start to her life when aged 12 her older brother was convicted of murdering their father. Later, she attended the art academy in Istanbul as one of their first female students. A controversial decision as the academy hosted living models, and was therefore not seen as a seemly place for young ladies.

She continued her studies in Paris in the late 1920s. In 1945 Zeid’s second husband Prince Zeid Al-Hussein of the Hashemite royal family was posted at London as the Iraqi Ambassador. The couple split their time between London, Paris and Ischia, Italy, where they maintained residences. Zeid’s work was well received by critics and gallerists, and she exhibited in the ICA in London and in the prestigious Katia Granoff Gallery in Paris.

Advertisement

Zeid never stopped making art during her long and eventful life. From the first competent water colour portrait of her grandmother aged 14, to the self-assured Self Portraitin 1944, to the late portrait Someone from the Pastin 1980, she continued to fill sketch books with drawings and motifs. In the late 1940s and into the early 1950s she concentrated on the large, dazzling, swirling abstract works for which she is best known.

The titles Fight Against Abstraction and My Hellreflect her inner artistic battle between figuration and abstraction. In My Hellthere are references to stained glass windows, Byzantine mosaics and the patterning of Persian rugs. In Fight Against Abstraction her truncated figures are often reduced to limbs or faces, coupled with clarity of transparent colour. Both the figurative and abstract works show how Zeid delighted in her engagement with paint.

Thanks to her privileged financial position, Zeid often travelled in airplanes and the aerial view from the plane was an influence on her increasing interest in abstraction. Nature, too, appealed to her, as a group of water colours painted while on holiday at villa in Ischia, in 1958, attest.

Fortunately Zeid and her husband were at the villa in 1958 when there was a military coup in Iraq that resulted in the assassination of the royal family.

The couple was given 24 hours to leave the embassy. Zeid’s days of entertaining were over. For the first time, Zeid without servants had to learn to cook. In a charming short film at the exhibition, she recalls a related epiphany: having seen her family reduce the Thanksgiving turkey to a bare skeleton, she went to throw it away but was struck by its sculptural appearance. She painted it in strong calligraphic forms mounted it on a slow-spinning motor.

It became her first sculpture using bones, a way of working she went on to call paléokrystalos. After her husband's death in 1970 she became increasingly isolated. In 1975 she moved back to Amman in Jordan to be with her youngest son. There she created an art school to support young women artists. She returned to portraiture often, depicting the large exaggerated eyes one associates with Byzantine works. She died in 1991, aged 89.

While Zeid is best known for her portraits and her large sparkling abstract, my favourites are her works from the early 1940s. Three Ways of Living (War) from 1943 lays down in immaculate patterning and design the dangers of war, with its right-flanked parade of incoming war planes about to destroy the central sunlit picnics, before giving way to the cold and empty monumental cemetery on the left side of the painting. Throughout her peripatetic life, Zeid drew and observed both Western and Eastern art. She learned from the rich opulent fabrics of western artists like Matisse, the landscapes of Cezanne and the subjects of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, in addition to observing the tiles, mosaics and Bedouin yoghurt sellers through the grates of her own city.

The result is a rich and rewarding body of work and an exhibition that will reintroduce Zeid to a new generation of art lovers.

The independent

Advertisement