Biography writing can be a fraught, delicate business — from choosing a worthy subject to ensuring the life writing becomes interesting to the reader. A biographer often has to deal with difficult relatives, conflicting stories, and embittered rivals. And writing an autobiography has its own set of problems.

That said, very few writers in English have done this work with greater finesse and honesty than Edmund Gosse, the writer of the first psychological biography in English, Father and Son.

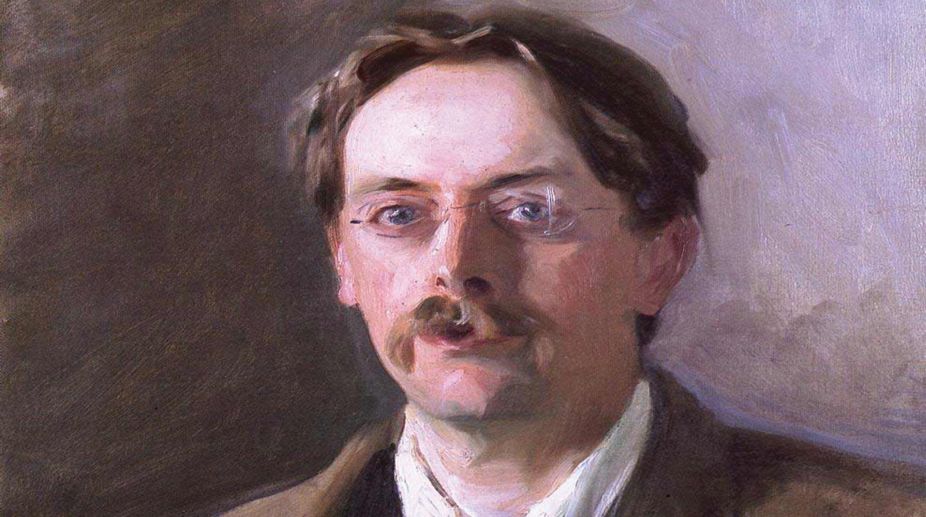

If we are asked to mention the name of most influential arbiter of taste during the last two decades of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th, no other name comes so easily to mind as that of Gosse (1849-1942), the critic and biographer par excellence.

Advertisement

Through readable essays and books pitched at a popular audience, Gosse helped the English reading public make the transition from the Victorian to the Edwardian and Georgian eras of literary history. Through his gift for literary biography, he helped to make accessible to the English common reader, a body of new writing which was, at first, difficult and intimidating.

His voluminous collected writings evidence a range of interests and expertise almost unimaginable in a critic today. For 40 years, it is not too much to say, Gosse was an accessible voice and face, of the British literary tradition; and with his crowing achievement, the autobiography and Bildungsroman Father and Son (1907), he paved the way for an entirely new, and modern, mode of life writing.

Edmund William Gosse was born on 21 September 1849 to two popular writers; his father Philip Henry Gosse was a naturalist, and his mother Emily Bowes Gosse, a writer of primarily education and religious tracts.

When the young Gosse, the couple’s only child, was just seven, his mother died of cancer, whereupon his father left London, and moved near the popular seaside resort town of Torquay.

Through the offices of his father’s friend, Charles Kingsley, Gosse was offered a clerical job at the British Museum at the start of 1867. His first venture into print was a volume of poetry in the manner of his friend AC Swinburne and Pre-Raphaelite poets; its decadent sensuality troubled his devout father, who paid for its publication with the provision that certain passages be rewritten or suppressed.

Gosse’s first impact in the field of criticism dates from 1872, when he published four essays on the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, at that time unknown in the English speaking world.

Gosse’s lifelong championing of Ibsen was to prove decisive as, over the next four decades, the British avant-garde, including writers like George Bernard Shaw and James Joyce, eagerly adopted Ibsen’s symbolist-related plays as the prototype of modern literature.

Gosse’s first sustained critical work was Studies in the Literature of Northern Europe (1879); building on his work on Ibsen, the term “studies” in the title suggests the work of both the scholar and portraitist, or biographer, for Gosse’s greatest talent as a literary critic lay in forging connections between the life of an author and the work.

Gosse moved from the Studies to a handful of biographies proper in the next half dozen years — Gray (1882, a life of the poet Thomas Gray), Raleigh (1886), and the Life of William Congreve (1888).

These biographies were impressionistic character studies rather than fact-driven scholarly biographies and were calculated to create an overarching impression of the character of a man — to convey a dominant feature or characteristic.

Gosse made his goal a true impression of his subject, a kind of subjective truth, and critics relished the opportunity to point out his frequent divergence from established fact. He also wrote in 1883, Seventeenth Century Studies: A contribution to the History of English Poetry, while also writing for both the Encyclopaedia Britannica and Sir Leslie Stephen’s Dictionary of National Biography in the spare time between his two projects.

We can see a measure of Gosse’s growing reputation in his lecture tour of the US in 1884, along with his appointment as Clark Lecturer at Cambridge University in that same year. In the following year, he published From Shakespeare to Pope: An Inquiry the Causes and Phenomena of the Rise of Classical Poetry in England, culled from his Cambridge literatures.

Like his literary biographies, it was attacked in some quarters for its loose adherence to facts, details had been sacrificed in the name of a larger argument about the alternating currents of classical and romantic writing in British literature; but it was precisely this emphasis on the big picture that made Gosse’s criticism so influential and so popular.

One of his early 20th century successors, TS Eliot, called Gosse the last English man of letters; and indeed in his range of literary topics, in the accessibility and popularity of his writing, Gosse has no equal in 20th century writing and beyond.

Gosse wrote for a British reading public that had never before been so large, owing to an increase in literary rates and innovations like lending libraries and cheap editions of the classics.

At the same time, literary pedagogy had but little to offer newly enfranchised readers, and in any event many members of the reading public had no formal training in literary application. Gosse became their schoolmaster. His 1889 study A History of Eighteenth Century Literature (1660-1780) may represent Gosse’s finest piece of scholarship.

In 1888, Philip Gosse died; Edmund quickly began work on a study in tribute, the biography The Life of Philip Henry Gosse, FRS, which was published in 1889. Taking his metaphor from his father’s own realm, the son sought to exa-mine his fa-ther’s life objectively and scientifically — as a naturalist would approach his own research subject, an attitude that he insisted was the only one his father would have approved of.

The resulting picture is not nearly as dispassionate as Gosse’s comments on method might suggest but the biography is finally memorable for the light it sheds on Gosse’s one indisputably major contribution to British literature, the autobiography,

.

In the meantime, Gosse’s reputation as an arbiter of public taste only continued to grow; he assumed roles in the Royal Literary Fund and the Society for Authors, and produced a novel (The Secret of Narcissus: A Romance, 1892), a volume on Jacobean poets (1894), a collection of essays on contemporary literary figures, Critical Kit- Kats (1896), and the ambitious survey of English literature from the age of Chaucer.

From 1904 until 1907, Gosse returned to his favourite form, the biography, publishing books on the 17th century Anglican writer, Jeremy Taylor (1905), the 17th century physician and writer Sir Thomas Browne (1905), and the 19th century poet Coventry Patmore (1905).

In 1907, Gosse published a monograph on Ibsen, and work on Ibsen seems to have strengthened his resolve for the courageous writing of Father and Son, published in the same year.

Dating back as far as his 1882 biography of Thomas Gray, Gosse had been at work in transforming the craft of the literary biographer, suggesting the mutually constitutive roles of life and art in such a study: the life of a writer is his writing, and his writing is the most significant event in his life.

Likewise, with Father and Son, Gosse, along with Samuel Butler (in The Way of All Flesh, published four years earlier), created a new model of the examined life for 20th century writers as diverse as Joyce, DH Lawrence, and Dylan Thomas.

Published anonymously, Father and Son chronicles the first 17 years of Gosse’s life, the last ten of those along with his father; in a pattern that has become familiar since its publication, the book details the struggles of a son to come out from under the shadow of his powerful father, to reconcile the warring claims of science and faith, to discover his life’s calling, and to discover a more authentic mode of living in a changing and utterly changed world.

The book is distinctively modern, if not Freudian, in its unflinching emphasis on the importance of sexuality in this life journey, as well as its eager adoption of fictional means in service of a more compelling presentation of the reality of the life.

In this work, Gosse had demonstrated that it was the tools of the novelist that were needed to do the job of the biographer convincingly. All 20th century life writing, including such sui generis hybrids as Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas (1933), and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928) are to greater or lesser extent in Gosse’s debt.

Having revolutionised the practice of literary biography and autobiography, and consolidated his position as the most influential literary critic of his era, the last two decades of Gosse’s career was rather muted, producing books on Robert Louis Stevenson (1908), on the political situation of Denmark (1911), a long-deferred biography of his friend Swinburne (1912), and a book on French literature (1918), among others.

Gosse was knighted in 1925; by the time of his death in 1928, owing to complications from surgery, he had long since passed on the baton of literary arbiter to another generation of literary critics, foremost among them being TS Eliot. But Eliot’s career as a public intellectual and man of letters would not have been possible without the example of Gosse.

Indeed, during the turbulent years of great literary and cultural upheaval, the seemingly imperturbable poise of Edmund Gosse to no small extent saved literary culture for the 20th century.

None today could, or perhaps would want to, practise literary criticism in the way that Gosse did for nearly 50 years; yet none today could practise it in the way he chose to, were it not for Gosse’s seminal example.

Advertisement