Magic realism in times of reflection

The book will be out in April 2024 and is billed to be gripping, intimate, and ultimately life-affirming meditation on life, loss, love, art—and finding the strength to stand up again.

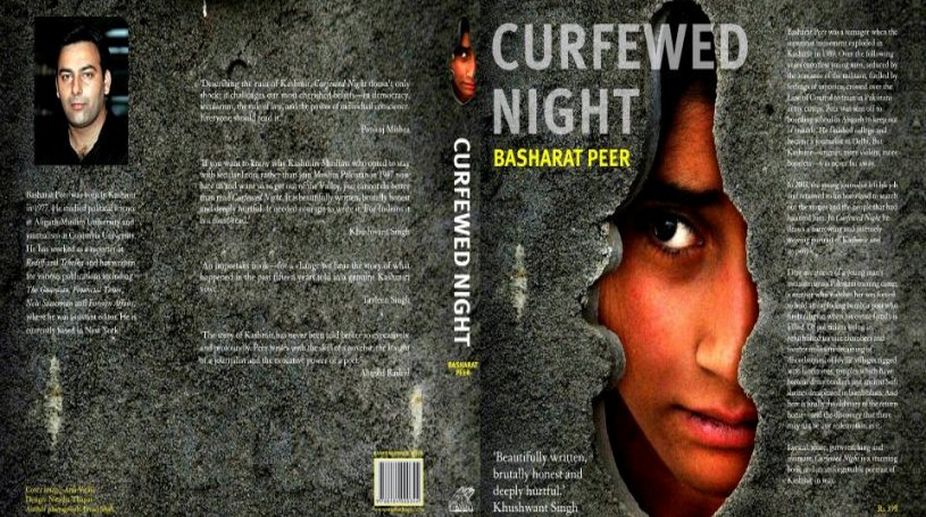

(Photo: Facebook)

In his book Curfewed Night (2009) Basharat Peer talks about how the bookstores of Delhi opened his eyes to the fact that countries with troubled histories like Palestine, Israel, Bosnia, Tibet and East Germany were being chronicled by their writers, whereas there was no one to write about Kashmir, a valley caught in the crossfire of Indo-Pak politics. Peer seeks to remedy the situation by writing Curfewed Night, a non-fictional record of his experience as a Kashmiri in the frightening times of the 1990s.

As the text unfolds, with growing misgiving we realise that Kashmir’s chief tormentor is the Indian Army the executor of every type of offence from intimidation to rape and torture.

One story stands out; that of a Shameema, a Kashmiri mother who is informed by her sons’ friends that her sons, Shafi and Bilal, have been picked up by the Indian Army and taken to a militant site close by. The mother rushes to the site fighting every soldier on the way. Shafi is already dead by the time she reaches the site. He had been sent into the militants’ building carrying a mine. The mine exploded and the boy was blown to pieces. The mother rushes in time to see the army chief place a mine in the hands of Bilal, her other son. She whips the mine out of Bilal’s hands and lashes out at the army men daring them to send her in his place. In the altercation some of the militants escape the cordon. The army finally consents to let the mother and son go and she is able to return with one son. At one point the little Bilal cries out, since Shafi is dead, he should follow his brother into the house. He wishes to die too…

Advertisement

The repugnance of Kashmiris for the Indian Army stems from betrayal and terror. Between the pincer-pressure of Pakistani militant groups like Lashkare-Toiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad on one side and the Indian army on the other, life in the valley grinds to a stand-still. In a rare bout of humour, Peer observes how the militants become the style icons for Kashmiri youth, "Kashmiri teenagers in the early nineties did not imitate Che Guevara and Malcolm X; militants walking the ramp of war determined the fashion trends. Militants wore Kamachi shoes and boys wanted Kamachi shoes. Militants replaced the stones in their rings with pistol bullets and boys replaced the stones in their rings with pistol bullets. To the Sufi tradition of wearing an amulet was added a Kalashnikov cartridge”.

Among other things it is hero-worship, a paucity of alternatives and travesty in the name of popular choice by elections rigged shamelessly by the Indian government that drive the boys and young men of Kashmir to cross over to the other side for arms-training and their return as JKLF militants.

Whether it is education or employment Kashmiris no longer have access to the best. Peer recollects how his teachers and his father’s Hindu friends were forced to leave their ancestral homes and are presently dwelling at subsistence level in poor houses in Jammu. Only banking flourishes in the valley due to the cash that is constantly pumped into the place by India and Pakistan as seduction strategy.

In his portrayal of Kashmiris, Peer gives priority to his middle-class background. The aura of tragedy is intensified by the increasing criminalisation of civil life. How the suspicion and constant spying of the Indian Army disrupt the life of the valley, scattering young men all over India and the world; how educated, wellintentioned young men find it difficult to rent accommodation in Delhi, is portrayed, in a true-to-life, reportorial style.

Peer’s representation lacks trimmings, flourishes and overtly emotional outbursts. As a writer he has confidence in his material. The carnage is ghoulish enough to merit attention without embellishments. Peer identifies sectarian violence as having its roots in class rather than religion.

However, Peer’s book is not solely about the chronicling of gradual and vicious stagnation of Kashmiri life. It is also an exciting repository of Kashmir’s consolidated Hindu-Muslim history.“Islam in Kashmir,” says Peer, “had borrowed elements from Hindu and Buddhist pasts; the Hindus in turn had been influenced by Muslim practices.”

A number of stories stand out. One is that of the 14thcentury Tibetan prince Rinchana who became the ruler of Kashmir. To consolidate his position, Rinchana, a Buddhist, decided to convert to Hinduism and consulted the Brahmin pandits of Kashmir. The pandits however fell into an argument concerning Rinchana’s possible caste-mark after his conversion. In the meantime, Rinchana met a Persian Sufi, Bulbul Shah who, in reply to his questions simply said, “There is no god but God and Mohammad is His messenger.” Impressed by the man’s simplicity, Rinchana converted to Islam.

The other story is that of Zainulabideen, the liberal king, whose reign from 1420 to 1470 is considered to be the golden age of Kashmir. He is also referred to as Bud Shah or the Great King. Zainulabideen’s contribution is the colleges he built, the generous grants he provided, the craftsmen who came to Kashmir at his invitation to teach Kashmiris the secrets of papier-mâché and carpet-weaving, the revival of theatre and music and the ending of the persecution of Hindus.

Peer rues how most of the historical monuments like Pari Mahal (built by Dara Shikoh) have been converted to army base camps. From its rich multicultural legacy of a shared Hindu-Muslim past, Kashmir has declined to a pool of lies, fear, betrayal and sadism. Laments Peer, “Two words had remained omnipresent in my journeys. Whether it was at a feast or a funeral, a visit to a destroyed shrine or a redeemed torture chamber, a story about a stranger or about my own life, a poem or a painting — two words always make their presence felt: militants and soldiers.”

The other writer who has been preoccupied with Kashmir throughout his career is controversial novelist Salman Rushdie. Rushdie confesses, “I have a particular interest in the Kashmir issue, because I am more than half Kashmiri myself, because I have loved the place all my life. And I have spent much of that life listening to successive Indian and Pakistani governments, all of them more or less venal and corrupt, mouthing the self-serving hypocrisies of power while ordinary Kashmiris suffered the consequences of their posturing.” (Step Across this Line, 305).

In three of his novels — Midnight's Children (1981), Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990) and Shalimar the Clown (2005); Rushdie draws attention to the mystique, magic and tragedy of Kashmir. In Midnight's Children Kashmir is associated with Dr Aadam Aziz’s childhood and youth. The figure that stands out in the Kashmir passages is Taj the boatman who regales the child Aziz with stories and later, having given up washing, begins to stink.

The story-telling motif associated with Taj is repeated every time Rushdie uses Kashmir as a setting. Much of the action in Haroun surrounding Rashid the professional story-teller, who mysteriously loses his ability after a personal crisis, takes places in a shikara on “Dull” Lake in the valley of K. In his autobiography Joseph Anton (2012) Rushdie recalls how he was bullied by the Penguin people to change the name of the Valley of K to some other name since Kashmir was a contentious Islamic issue and Rushdie was already neck-deep in trouble over his The Satanic Verses (1988). With characteristic obstinacy, Rushdie stuck to his guns and finally got his book published by Granta.

Rushdie’s chief argument in retaining the name Valley of K is his conviction that the connection between Kashmir and story-telling is timeless. Katha Sarit Sagar the giant classical compendium of tales is a composition of Kashmiri pandits of yore. Therefore, a narrative based on the plugging and unplugging of the common magical fount of stories can only be set in the Valley of K.

Taj the boatman stands out in his capacity to regale the child Aadam with stories. But the adult Aadam witnesses a change in Taj, who loses his good spirits and grows unbearably dirty and smelly. The rapid deterioration of Kashmir from jannat (paradise) to dozakh (inferno) is perhaps hinted by Taj’s alteration.

The text that centralises Kashmir and concentrates on its political entanglements is Rushdie’s 2006 novel, Shalimar the Clown a text that begins by depicting Kashmir as prelapsarian paradise and ends on a bleak dystopian note. The multicultural concept of Kashmiriyat is highlighted by a plot centering on Pachigam a village inhabited by Hindu and Muslim bhands (theatre workers) and cooks, cuisine and theatre being major strengths of pre-military Kashmiri way of life.

The love between the Hindu girl Boonyi and Muslim boy Shalimar, encouraged by their fathers Pandit Kaul, the classical scholar and head cook and Abdullah the director of the theatre company of the village, indicates an edenic amity and peace that animates Kashmiri lives till all is shattered by growing IndoPak animosity that culminates in violence and complete destruction of Kashmiriyat. Shalimar, the dancer-actortrapeze-artist, madly in love with his childhood sweetheart Boonyi, transforms into a deadly sniper-militant trained by Pakistani and Afghan militants. His sweetheart now becomes his sworn enemy.

Shalimar the Clown is more of a fable than an allegory. The simple tale of love across religions is rendered vicious and intricate by the advent of the American ambassador Max Ophuls, a libidinous man who seduces and in turn is seduced by Boonyi who leaves with him. Boonyi’s departure pulls Rushdie’s narrative out of the pastoral precincts of Kashmir into the larger political and social arena of America’s treacherous involvement in Indo-Pak Kashmir-centred politics.

Shalimar the Clown, while being a morose and pantomime-like take on Kashmir’s social and political vitiation, is also a celebratory chronicle of what Kashmir was in her pre-lapsarian, edenic days, especially in its first half. In loving detail, Rushdie charts the mind-boggling multiplicity of her botanical wealth, the talents of her denizens in the realms of cookery (wazwaanor the banquet of thirty-six dishes minimum), theatrical histrionics (especially plays centering on Zainulabidin’s golden rule), and scholarship (Pandit Kaul’s untiring interpretation of classical texts).

In his book of poems evocatively titled Country without a Post-office, Agha Shahid Ali mourns the passing away of the immense greatness and sweetness that was Kashmir, “At a certain point I lost track of you. / They make a desolation and call it peace. /… Who is the guardian tonight of the Gates of Paradise? / My memory is again in the way of your history /… I am being rowed through Paradise on a river of Hell: Exquisite ghost, it is night. / … If only somehow you could have been mine, what wouldn’t have happened in this world? / I’m everything you lost. You won’t forgive me. / My memory keeps getting in the way of your history.” (from “Farewell”)

Shahid is right when he talks about personal memory getting in the way of political history. Basharat Peer, the Vodafone Crossword prize-winner for non-fiction, Salman Rushdie who lays huge premium on the novel as repository of lost history and Agha Shahid Ali, regarded as a great Kashmiri poet; all rely on personal memories in their representations of the Kashmir that has been perhaps destroyed forever. What history has obliterated for its selfish political ends, art has preserved with care and acuity. Today, in order to appreciate the truth of the famed lines, “If there is paradise on earth, / It is this, it is this, it is this”; it is to art, and not reality, that we turn; art that scrupulously and courageously recalls and recreates the annihilated charm and elegance that once upon a time was Kashmir.

Advertisement