Jaishankar to visit three ASEAN countries next week

External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar will be on an official visit to the ASEAN countries of Singapore, Philippines and Malaysia from 23-27 March.

(Photo: Getty Images)

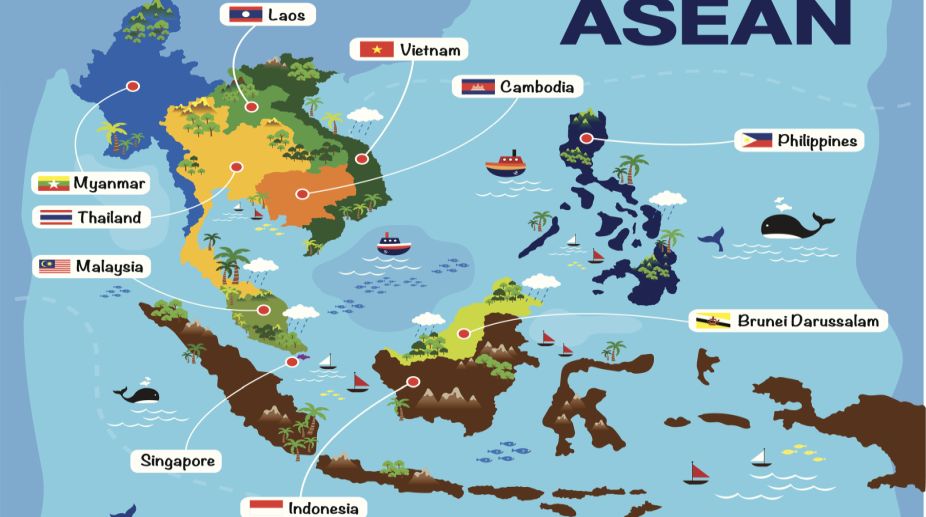

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), which marks its 50th anniversary on August 8, finds itself at a crossroads.

How can it continue to be relevant as a regional bloc, in the light of its inability to counter, or even merely criticise, expansive Chinese ambitions in the South China Sea? One possibility is for individual members to separately invoke last year’s arbitral tribunal ruling.

That landmark ruling in international law which the Philippines sought and which benefits individual member-states and the Asean as a regional association has been temporarily set aside by the Philippines.

Advertisement

The “Award” – decided by the arbitral tribunal convened under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – was released on 12 July 2016, a mere 12 days after Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte assumed office. His initial instructions were simple and forthright: provide “a soft landing.” What this meant, in the beginning, was for the Philippines to avoid gloating over the legal victory and rub China’s face in it.

What this means, a year later, is that the much more pro-China administration Duterte heads has effectively shelved the ruling, in favour of closer cooperation with Beijing. But while it was the Philippines which brought the case, it wasn’t the only interested party in the Asean.

Three other members have claims to parts of the South China Sea or the Spratly Islands or the Paracels that conflict with China’s expansive nine-dash theory: Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Indonesia, Asean’s largest economy, has continuing runins with Chinese fishing vessels and occasionally with the Chinese Coast Guard in its exclusive economic zone.

As the ruling itself noted, five Asean members sent official delegations to observe the hearings at The Hague in the Netherlands: Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand (with the Philippines the five original members of the regional bloc), plus Vietnam.

The Philippines’ setting aside of the arbitral tribunal ruling thus provoked consternation in Asean capitals, in large part because they had seen the logical progression of the Philippines’ legal approach to the disputes with China. The Award gave the Philippines, and by implication Asean and its members, genuine leverage over China by delegitimising Beijing’s belated claims of historic rights to almost all of the South China Sea.

The Philippine case against China was so carefully prepared, and the Award so carefully calibrated, that its findings can be invoked by other countries. The tribunal took pains to emphasise that it did not have the power to rule on issues of sovereignty.

“None of the Tribunal’s decisions in this Award are dependent on a finding of sovereignty, nor should anything in this Award be understood to imply a view with respect to questions of land sovereignty.”

Also, the Tribunal “has not been asked to, nor does it purport to, delimit any maritime boundary between the Parties or involving any other State bordering on the South China Sea.”

This obsessive consideration of its limits heightened the impact of the Award’s most famous, and most sweeping, finding: The tribunal “DECLARES that, as between the Philippines and China, China’s claims to historic rights, or other sovereign rights or jurisdiction, with respect to the maritime areas of the South China Sea encompassed by the relevant part of the ‘nine-dash line’ are contrary to the Convention and without lawful effect to the extent that they exceed the geographic and substantive limits of China’s maritime entitlements under the Convention; and further DECLARES that the Convention superseded any historic rights, or other sovereign rights or jurisdiction, in excess of the limits imposed therein.”

Given such an overwhelming legal victory, the Duterte administration’s “soft landing” approach took its Asean partners aback. A year after the Award was handed down, however, it is possible to argue that other Asean capitals are recovering from the shock.

Last month, Indonesia renamed the waters off its northern perimeter the “Laut Natuna Utara,” the Northern Natuna Sea. The Natuna Islands border the South China Sea, and its waters have been a low-intensity battleground between a special multiagency task force set up by Indonesian President Joko Widodo and Chinese fishing vessels.

Last year, to help mark Indonesia’s independence day, Jakarta blew up over 60 foreign fishing vessels it had seized. Whether the renaming is mere “nationalistic posturing” or part of a new campaign to push back against Chinese expansionism, the presentation of Indonesia’s new official map was significant for another reason. It invoked the 12 July 2016 arbitral ruling.

As analyst Evan A. Laksmana has noted: “The July 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling … was invoked to justify the ‘expansion’ of Indonesia’s EEZ in its border with Palau by assigning Tobi Island, Helen Reef and Merir Island a 12-nautical-mile enclave rather than a 200-nautical-mile maritime entitlement.”

While this designation “remains subject to negotiation,” Indonesia’s reference to the arbitral ruling marks the first official government use of a decision included in the Award. Beijing did not look benignly on Jakarta’s renaming and referencing. A spokesperson for the Chinese foreign ministry offered a simple retort.

“The so-called change of name makes no sense at all and is not conducive to the effort of the international standardisation of the name of places.”

To be sure, one new official map does not make a new international order. But if other Asean countries were to invoke the judicious decisions of the arbitral tribunal in the Philippines vs China case, it may strengthen the status of the Award as international law, encourage other countries to assert their maritime rights against China’s now-delegitimised nine-dashline, even embarrass the Philippines into a more assertive reception of the ruling it had fought hard for.

One result would be a regional bloc that can push back against Chinese expansionism, not because of collective action, but because of individual initiatives like Indonesia’s renaming of the North Natuna Sea.

Call it mini-minilateralism.

(The writer is Associate Editor and Opinion Columnist at the Philippine Daily Inquirer. This is a series of columns on global affairs written by top editors and columnists from members of the Asia News Network and published in newspapers and websites across the region.)

Advertisement