NSA Ajit Doval conferred with honorary degree by Central University of Punjab

Ajit Doval was awarded the Degree of Doctor of Literature (D.Litt.) (Honoris Causa) for his exemplary service to the nation.

(Photo: Facebook)

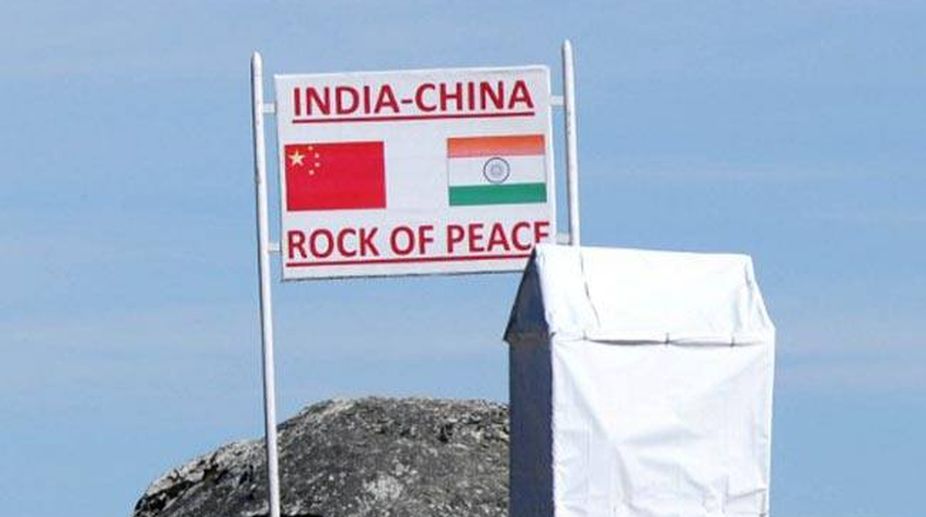

As is evident from China’s occasional reference to the punishment which it had meted out to India in 1962, it is toying with the idea of repeating the feat but is hesitating because it is uncertain about an adverse international reaction.

As the Indian External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj, has pointed out, the world chancelleries are almost unanimously on India’s side. In India’s immediate vicinity, there is little doubt that countries like Japan, Vietnam and Taiwan are with India.

If this is indeed the case, then China has only itself to blame. The aggression it has shown towards its neighbouring countries with their respective claims on the zones of influence in the South China Sea has made the international community aware of its bullying nature.

Advertisement

Although the longstanding apologist for China, the Australian journalist, Neville Maxwell, has said that China has settled its border disputes with 12 out of 14 neighbouring countries – the only exceptions being India and Bhutan – the falsity of the claim is evident from the maritime controversies in the South China Sea.

China, therefore, continues to be an unsettling presence in the region – somewhat like a more dangerous North Korea. Maxwell also says that India is repeating its 1962 mistakes by “violating” Chinese territory, but some observers believe that the Doklam standoff at the trijunction of India, Bhutan and China is a diversionary tactic which has been undertaken by Beijing at the request of its all-weather friend, Pakistan, to deflect the heat which Pakistan is facing because of the aggressive response by the Indian army along the border in Jammu and Kashmir to infiltrations from across the Line of Control and the shelling by Pakistani forces.

These observers rule out any escalation, therefore, in Doklam since China is playing Pakistan’s game and not its own. At the same time, China cannot be unaware of the implications of India fobbing off its bellicose intentions. Since China considers itself far superior to India, it simply cannot afford to be seen being held to a draw by a supposedly weak India.

To its neighbours and the rest of the world, such an outcome will be typical of a bully whose bark is worse than its bite. China, therefore, is in something of a bind for the first time since it began seriously flexing its military muscles. The forthcoming 19th congress of the Chinese communist party has further complicated the situation, for President Xi Jinping cannot afford to be stared down by India when he is seeking another term.

Even a mutually agreed simultaneous withdrawal of the troops will be interpreted as a defeat in China, especially by its gung-ho official media which probably reflects the more jingoistic among the apparatchiki. China wants, therefore, India to withdraw first before any negotiations can take place. But New Delhi’s refusal to do so cannot but have surprised Beijing which has – correctly – seen in the show of defiance a sign of the Narendra Modi government’s Hindu nationalist fervour. Clearly, the standoff has become a case of Han versus Hindu obduracy in the frozen landscape of the Himalayas.

The present confrontation between the two giant neighbours is a far cry from what Deng Xiaoping said about the need for solving the border disputes through “repeated discussions”, adding that until a settlement is reached, “let us develop contacts in other fields”.

These contacts have indeed been developed, mainly in the field of trade and commerce, which is another reason why a wider conflict is unlikely as it will disrupt the $ 70 billion bilateral trade and cast a shadow on China’s pet Belt and Road Initiative.

But even if there is no war, the fact remains that China has gone out of its way to be hostile towards India by befriending India’s inveterate enemy, Pakistan, opposing India’s entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group and preventing the UN from declaring the Jaish-eMohammed chief, Masood Azhar, as a terrorist. China, on its part, probably believes that India, too, has shown its unfriendly intentions by letting the “splittist” and “public enemy No. 1”, the Dalai Lama, live in India and even visit Arunachal Pradesh, which China describes as “southern Tibet”, against vociferous protests by Beijing.

But India has long been the preferred destination of those fleeing persecution, whether they were the Parsis from Persia in the 8th century, who were escaping from Muslim invaders, or the Tibetans in the 20th century who were running away from the Chinese invaders.

It is noteworthy, however, that despite the eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation in Doklam, China had no objections to visits by various delegations from the saffron think tanks.

The conversations of India’s national security adviser, Ajit Doval, with his Chinese counterpart and his meeting with President Xi Jinping along other NSAs showed that the lines of communication have remained open. India and China are seemingly entering a new phase of their relationship where they are more or less on an equal footing, for China has realized that India is no longer a pushover as in 1962.

It has also understood that there is more to international relations than military prowess.

(The writer is a former Assistant Editor, The Statesman)

Advertisement