Whiff of mismanagement in Bangiya Sahitya Parishad

The annual general meeting of Bangiya Sahitya Parishad is going to be stormy in view of the sheer mismanagement of the authorities running the organization.

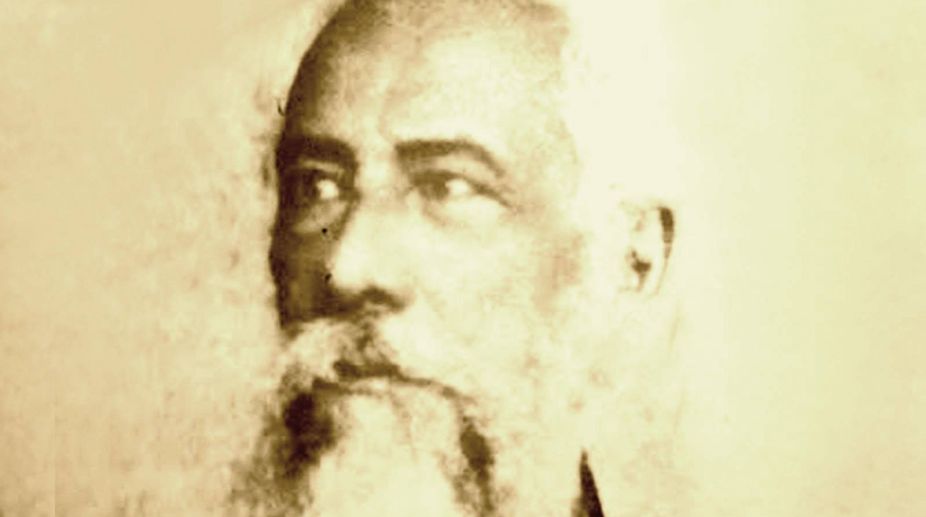

Debendranath Tagore (Photo: Facebook)

This year is the bicentennial of Debendranath Tagore (1817- 1905), the eldest son of Prince Dwarkanath Tagore, who was also known as Maharshi, or the “great sage”. It was during Dwarkanath’s lifetime that the Tagore family’s fortune grew to almost unbelievable proportions, albeit to be quite completely lost with his death. It took much privation, sacrifice and effort on the part of Debendranath to clear the debts left behind by the Prince.

However, wealth and fortune were really incidental to the lives of the Tagores; their uses tell us much more about them, and fill us with reverence and awe. The members of the Tagore family seemed to have been endowed with the ability to not only engage in public good but also to strike out in new directions in their lives, thereby impacting the sensibilities of prevalent social norms. Clues to this tendency can be discerned in Rabindranath Tagore’s own words, “We seemed to enjoy the freedom of the outcaste. We had to build our own world with our own thoughts and energy of mind…” These words find their echo in Satyendranath Tagore’s (Debendranth’s third son) introduction to the autobiography of the Maharshi (1916, London) where he is trying to explain the distinctive path chosen by his father in his stewardship of the Brahmo Samaj, “…Reason and Conscience were to be the supreme authority and the teachings of the scriptures were to be accepted only in so far as they harmonised with the light within us.”

The Tagores dreamt dreams, their imaginations were heightened, and their sensibilities directed more at the higher realms of philosophical sublimation than at everyday existence. Many conjoined forces, religious, social, cultural, political and historical were sieved through their dreams, philosophical ideas and attitudes; the ultimate results were the creation of new paths for both the individual and for the Samaj. Theirs was not the spirit to balk at the effort needed and the strains endured in materialising their dreams.

Advertisement

Debendranath, “both saint and sage, was truly the heir and successor to Rammohun Roy” (Krishna Kripalani). Early in his life he realised the futility of material wealth unless it is used for public good. He also had an immensely powerful religious experience that turned him away from the practices of the Hindu religion; he felt strongly that it needed the robustness of the ancient texts and that the time-worn tenets of the Hindu faith had to be re-defined. He felt too that they had been brought to public notice thus in the works of Rammohun Roy in order to transform and revive a moribund society bereft of all pride, and wallowing in superstition. His personal experience of this realisation was fraught with internal conflicts but in his actions he showed a mind and hand steady in the pursuit of the understanding of the Upanishads.

It is often asked if the future learns from the past or if history is smug in its “I told you so”, and rests its argument on the premise that humans are prone to repeat themselves. The accounts of Debendranth’s battles in the firmament of his ideas (chronicled painstakingly by Ajit Kumar Chakraborty, 1916 Allahabad, Sri Debendranath Thakur) were no different from the irrationality of blindness and conservatism that is seen and experienced today, even at the distance of two centuries. The truth that stands out is that every school of thought and philosophy spawns the conservative and fundamental idea that bypassing all reason seems to possess a telling power that can hound anyone who is seen as the betrayer from even the same fold.

The history of the Brahmo Samaj and the Brahmo Dharma, torchbearers of the “modern Indian ethos”, is intimately linked to Debendranath’s efforts. He believed that the idea of one Supreme Being encompassing nature and the cosmos could be a means for collective stimulation of creativity and ananda, two necessary ingredients of self-determination and self-assurance in confronting the stifling and waning situation created by blind superstitious faith that the Hindu religion had been reduced to. It was only natural that this modern day seeker of truth and the meaning of life would find a spot which embodied his deep realisation of moner ananda, atmar shanti, praner aram in Santiniketan and transform a desert into an oasis of spirituality, creativity and intellect. In the process he was able to create not just a space for like-minded Brahmo members but also a place where common people of the surrounding areas could also have access. The Pous Mela trust deed enjoins the display and performance of folk art, artisanship and culture beyond the bindings of creed and caste. Even to this day, a portion of the mela is a showcase for these aspirations.

Debendranath was a man of superior intellect; he was also a voracious reader to the end of his days — he had keen interest in assiduously pursuing the study of various languages. He knew English, Persian, Sanskrit, and Gurumukhi and took up French when he was fairly old. His favourite poet-philosopher was Hafeez, whose works gave him solace and inspiration. He had read Kant, Fichte, Francis Newman, Tennyson, Amiel, and the Bible, along with the leading Bengali thinkers. At the age of 18 he wrote a book on Sanskrit grammar and prolifically contributed to the issues of the Tattvabodhini Patrika. He transcreated the Upanishadic verses and devoted his time and energy to writing the philosophical arguments of Brahmoism.

His attention to the education of the children of his household was unabated to the last; he always had about him volumes on varied subjects by which he could transfer knowledge to the children — volumes on geography, geology, biology, anthropology, astronomy, history. He was deeply attracted to science. Debendranath would read and explain the complex ideas from these volumes to the children around him.

Reading the accounts of Maharshi’s travels in the various parts of the country especially his travels and treks in the Himalayas, provides one with a glimpse of his strength, endurance, tenacity and skill. His ability to embrace the simplest and most basic living conditions and in making the local people his own was legendary. Debendranath was always attracted to nature’s beauty in his travels — the mountains, the seas and the rivers were his preferred places, which he used as retreats from the material world. However, he did not neglect the responsibilities of his large family of which he was the respected and revered pater familias.

Of all his 14 children, Debendranath was closest to Rabindranath as the poet possessed many of the ideals of his father. Rabindranath time and again acknowledged his father’s influence in his life and work, and a large part of his public engagement was taking his father’s work forward, thereby shaping and strengthening his ideas of modernity. Debendranath was a product of the Bengal renaissance ushered by Rammohun Roy and in Rabindranath that renaissance was fully actualised.

The author is professor, department of social work, visva–bharati

The daily star/ann

Advertisement