Modi speaks to Italian PM Georgia Meloni, thanks her for Italy G7 Summit invitation

The G7 Summit is scheduled to be held in Italy from June 13-15.

(Photo: Twitter)

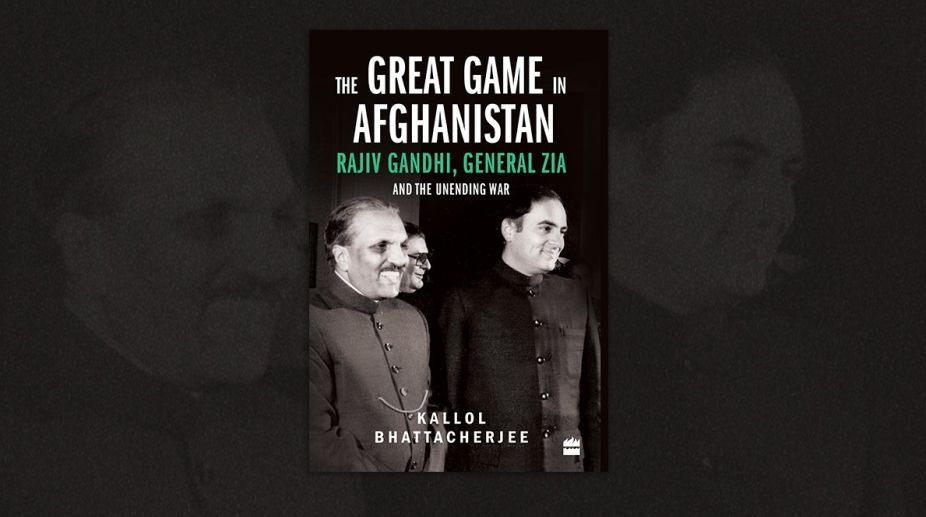

Bhattacherjee’s book is a specimen of breathless modern history told by someone who thinks he is scooping the world. His heroes are obvious — former US ambassador to India John Gunther Dean, Rajiv Gandhi, and former Indian ambassador Ranendra Sen to whom he invariably refers by his nickname, “Ronen”.

Through his contacts with Dean and to a far less extent, Sen, Bhattacherjee unfolds his version of Gandhi’s initiatives to stabilise the postconflict Afghan situation after the Soviet withdrawal, which never in fact added up to much and eventually collapsed.

The same narrative could be portrayed as another example of Gandhi’s naiveté as a novice in international diplomacy. It is unwise to rewrite history on the basis of hero-worship. The records used to justify Bhattacherjee’s thesis are from the US and Dean’s personal collection and as usual not from Indian archives, whose unnecessary closure defy efforts to arrive at an authentic version of India’s position.

Advertisement

The author posits Sen in the role of intelligence-cum-diplomatic vizier to Gandhi — though it is unlikely that Sen himself subscribes to this view —and astonishingly never cites any contact with MK Narayanan, who then occupied the key intelligence role, or MS Aiyyar, who was privy to Gandhi’s thinking on world affairs.

The closeness of Sen, Narayanan and Aiyyar to Sonia Gandhi as a result of their work with her husband brought them later appointments under successive Congress governments but that is another story.

The core argument is that Gandhi “connected all sides (USSR, US, Pakistan, the Aghan leadership) creating the contours of a political consensus” namely a non-aligned broad-based Afghan administration guaranteed by the major interested powers.

Despite the flaunted friendship between Gandhi and Reagan and Bush, the US let Gandhi down on the “bargain that they had made” on Afghanistan and Pakistan’s nuclear status, which meant that the “peace effort” was doomed.

The fall of Najibullah was another failure of Gandhi’s making. Rajiv Gandhi’s other diplomatic initiatives — disarmament, environment, third world economic cooperation —like his Afghan proposals came to nothing because they did not take into account that the world was changing to a US-dominated sphere.

What the author regards as Gandhi’s “talent for diplomacy” was in reality negligible. India was in no position politically or economically to play in the big league and being consulted by the US did not imply dining at the high table. It is fanciful to think that the US and USSR needed a go-between or “secret Indian channel” between the White House and Kremlin, and such claims suggest that the author’s informants sought to magnify their role.

The quid pro quo of India’s help to resolve the Afghan issue was the US reducing its arms supply to Pakistan, which has been a naïve Indian assumption of Indo-US amity ever since the 1950s.

As could have been foreseen, US arms to Pakistan continued even as the Soviet pullout was imminent, making Indian assumptions ridiculous. The author sadly concludes the “mujahideen were not willing to play by the rules” and the Americans “preferred the Pakistani leaders to India’s.” Bhattacherjee gives too much importance to backstairs intrigues and off the record talks and indulges in gross exaggerations.

He describes Sen and Dean “often coordinating on issues of interest on a daily basis” which is ridiculous to anyone who has worked at high levels in the government. He writes that Pakistan president Zia’s death/murder in an air crash could spark a nuclear war between India and Pakistan —more than a decade before India and Pakistan tested nuclear weapons. He is fond of the word paranoia, used thrice on the same page.

He claims “it was obvious to Rajiv and his team that the USSR was not going to last long”, which would be news to everyone including the US and Gorbachev. The text is not free of absurdities; “As an ex-intelligence officer, he knew that news is often the best tool for private investigation.”

The author writes that British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher stopped over for an hour at Bombay airport in 1984 due to the murder of the UK top diplomat in that city, and the Maharashtra home secretary was “surprised” she did not mention the matter — which he regarded as sinister. Senator Charles Percy was Gandhi’s “secret lobbyist in Washington DC.” At another place, it is said that Zia “wanted to delay history.”

The editors at HarperCollins are generous with cli-chés, including the Great Game of the title and eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation. They also do not know the difference between “defuse” and “diffuse”. In sum, this is an unconvincing book and a waste of considerable research that should have been put to better use. Also about Pakistan/Afghanistan but of a very different nature is Nate Rabe’s racy, fast paced novel,The Shah of Chicago, about a shambolic effort to enter the illegal narcotics trade.

The anti hero is an unattractive jive-talking American junkie of Pakistani origin who returns to his country of birth to get rich quickly. He is a criminal ex-convict murderer but a lover of ghazal and Bollywood.

While his narcotics enterprise bombs, a totally improbable love life with a high-society Pakistani woman flowers.

This whole text is so full of outlandish stereotypes that it strains credibility, as indeed does the strange name of the author. But it makes for easy reading as a spoof compared to Bhattacherjee’s distorted presentation of the Great Game.

(The reviewer is India's former foreign secretary)

Advertisement