R Madhavan had a real-life ‘3 Idiots’ moment with his father

Madhavan shares a touching anecdote, reminiscent of a scene from "3 Idiots", reflecting on a heartfelt conversation with his father about career aspirations.

A bureaucrat lives in a rambling mansion next to a fish-filled pond but once he crosses the Howrah Bridge, cruel realities threaten his idyllic existence.

The younger generation would remember author Jayant Kripalani as the interview panel head in blockbuster film, 3 Idiots, based on Chetan Bhagat’s first book, Five Point Someone. For the older generation, the actor was a familiar face on television, playing roles in Khandaan, Mr Ya MrsandJi Mantrijiwith a flair that put him squarely in the Hindi film and TV firmament. He also played character roles in the 1983 film Heat and Dust directed by James Ivory,Rockford(1999) and The Hunger.

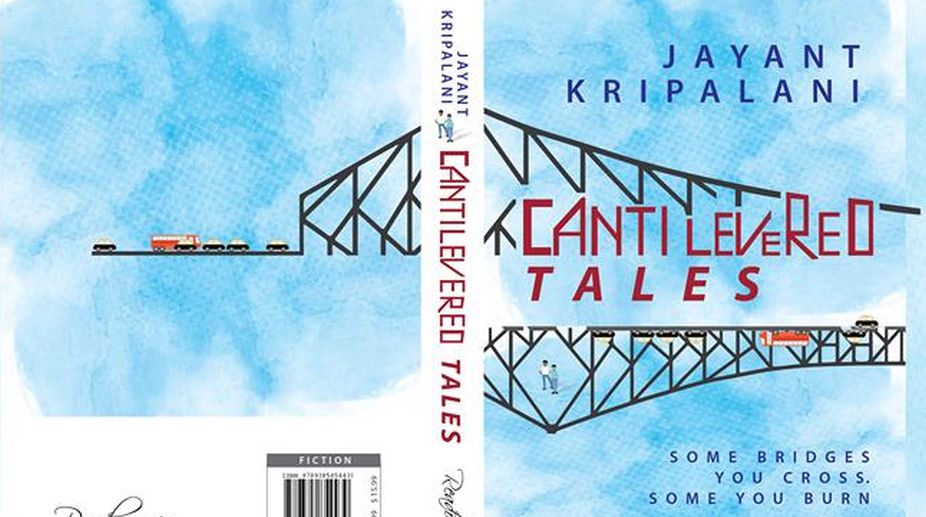

A graduate of Jadavpur University, he has clearly steepedhimself in Bengali culture, as was clear from the 1960s nostalgia that soaked his first book, New Market Tales, now an e-book on Kindle. After 30 years in Mumbai, he returned to Kolkata and now gives us Cantilevered Tales, a book that is at one level a mocking social satire and at another a scathing indictment of the land mafia. The title, of course, refers to the Howrah Bridge, on which traffic jams in rush hour symbolise a stagnant life, filled with frustration and longing to get off the gravy train. On the other side of Howrah Station, he writes, was “the gateway to our personal lives, away from the humdrum of our underpaid, underworked jobs in government offices.”

Advertisement

The protagonist, we learn is a bachelor to whom nobody (in the novel) ever poses the question of marriage, a curious circumstance in Indian society. After joining the civil service, he works in Writers’ Buildings and lives with his widowed mother in a 20-room mansion next to a pond from which a faithful retainer could always extract fresh fish for the dinner table and for the market, not to speak of the fruit trees with their bountiful harvest. This is where he sits contentedly smoking his father’s hookah. What more could a bhadralok want?

However, time and tide await no man’s pleasure. Which is why, one hot summer’s day, “There appeared a man in a three-piece, pin-striped suit. He was tall, had longish, slicked-down-withgel hair, parted down the centre, and a well-groomed beard that covered most of his face. He was good looking in a Columbian drug lord kind of way as portrayed in later Hollywood movies.” The intruder — indeed, the villain of the piece — is a member of the property mafia, who wants to convert the protagonist’s seven-acre property into a resort or conference centre, with the pool being transformed into a state-of-the-art swimming pool.

This, then, is the central conflict of Kripalani’s story.The love of property — a la Manderley inRebeccaor TarainGone with the Wind — remains the motivation that moves the drama. Charming characters drop in and out —a bird-watching family, a chief minister whose humour and incorruptibility hint at Jyoti Basu, an advertising guru who seems very Alyque Padamsee. And that other Kolkata institution, The Statesman. Let us self-indulgently reproduce the following review of one of the city’s oldest bars, Chhota Windsor, by Hamdi Bey ofThe Statesman, about whom a character says, “They don’t make writers like him anymore.”

“What is attractive about the place is indeed the tough, male aggressive attitude of the entire establishment: the company is cheerful, even boisterous, but there are few brawls for everyone stands in awe of the bartender, who has never tasted a drop himself and who is known to raise a finger to stop a waiter from serving that last lethal drink to one who is already drunk…Faithful habitues just love this air of firmness and overbearing honesty. They perhaps crave that discipline and would obviously like to be spanked by the younger waiters now and then.”

Kripalani’s writing style is quite like his acting — all self-deprecatory humour and understated realism. A hint comes in the sub-title, “Some bridges you cross. Some you burn”. As the action unfolds, the reader looks forward to phrases like “wild horses and wilder ministers” and “suddenly he was like a sail without a wind” that pepper the narration. Or a real gem, “Of course, if he ever found out that I had thought of his face as petulant, he’d castigate me and march me out of the service faster than a bureaucrat passing a buck.”

As the plot unfolds, there is a Bollywood-style climax complete with dancing girls in skimpy clothes — the fictitious headline in The Statesman, was “Some Migratory Birds are Welcome to Stay”. And a denouement that doesn’t really impress — a “childhood trauma” explanation of why the property shark had become what he is. It seems more likely that property sharks develop their ruthlessness and sense of invincibility thanks to political patronage and the homing instincts of a burgeoning middle class that does not own acres of land in the city.

The blurb says “This is NOT a Builder v Helpless Citizen epic” even though the idea was sparked by a group of people wanting to save a water body from an unscrupulous builder. Many readers will appreciate the idea of preserving the old-world charms of a more leisurely life but others might be left wondering why a man of considerable means should not relocate permanently to the Kullu Valley, leaving the frenetic city to continue its march to progress. Didn’t a certain cantilevered bridge take the place of an 1874 pontoon contraption 75 years ago?

The reviewer is Senior Editor, The Statesman, New Delhi

Advertisement